The world has experienced an exceptional couple of years. Aside from the millions of casualties, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed much of the world in recession, disrupted supply chains, and dried up tourism, an important source of revenues. The pandemic and the differential policy response also increased inequalities between north and south, and aggravated tensions within countries between the haves and have nots. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine added to the misery by causing a spike in energy prices and food prices, the latter of which hit developing countries disproportionally as food constitute a much higher share of household spending at low income levels compared to high income. Several developing countries are now faced with insurmountable debt problems, and despite the G-20 debt service relief initiative, may face disruptive debt default such as Sri Lanka recently experienced.

In this environment it is easy to lose track the most pressing problem of our times: climate change. The science has been settled for some time that human-made climate change poses a considerable threat to the environment, living standards and livelihoods across the globe. It is also clear what needs to be done: a massive investment in mitigation to prevent temperatures to increase beyond 1.5-2 degrees above pre-industrial levels and massive investment in adaptation to adjust to the effects of even minor climate change—heatwaves, sea level rise, storm intensity rise, and more.

But who should do this? Or better, who should finance this? Should countries such as Cambodia, a lower middle income country with only 16 million people, divert resources to fight climate change, or should it focus on other priorities, such as education, building infrastructure, and improving government administration?

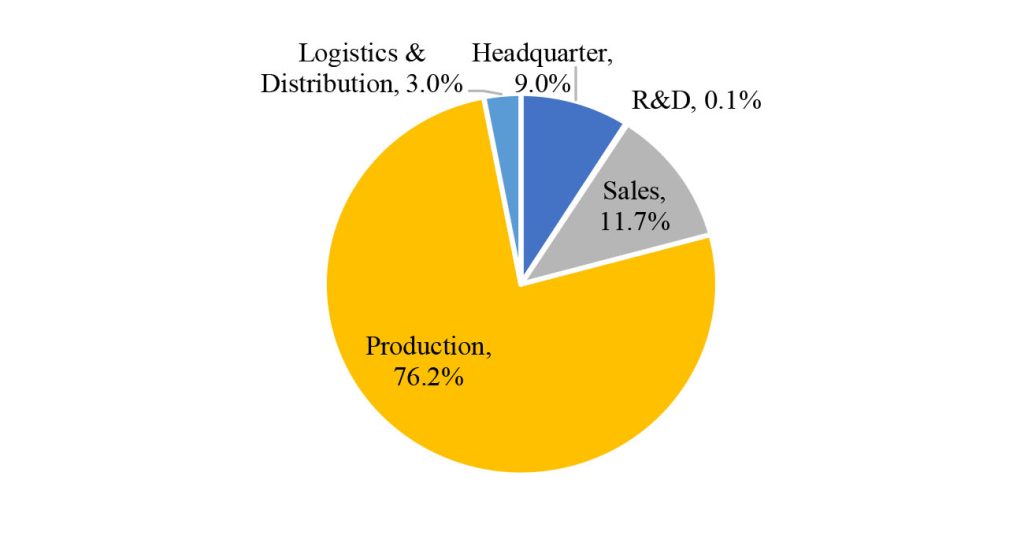

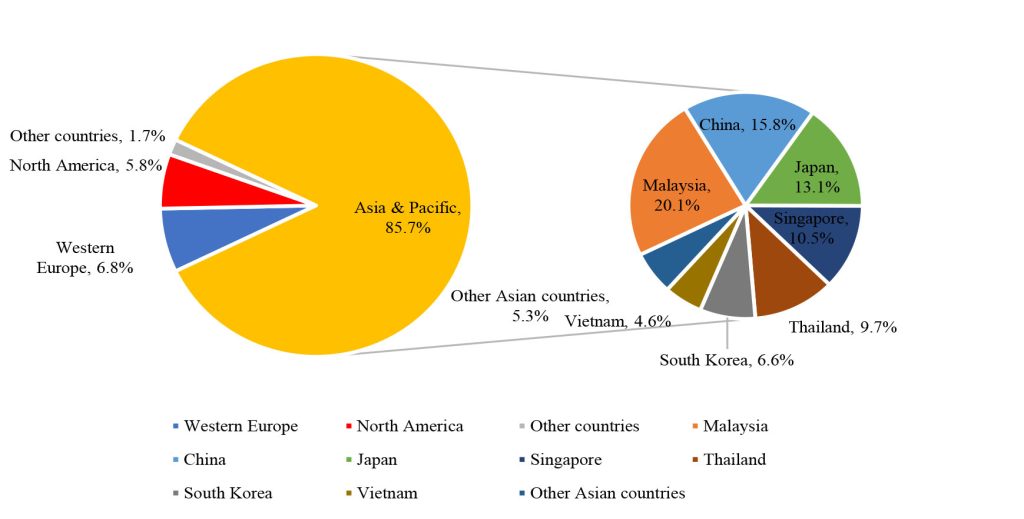

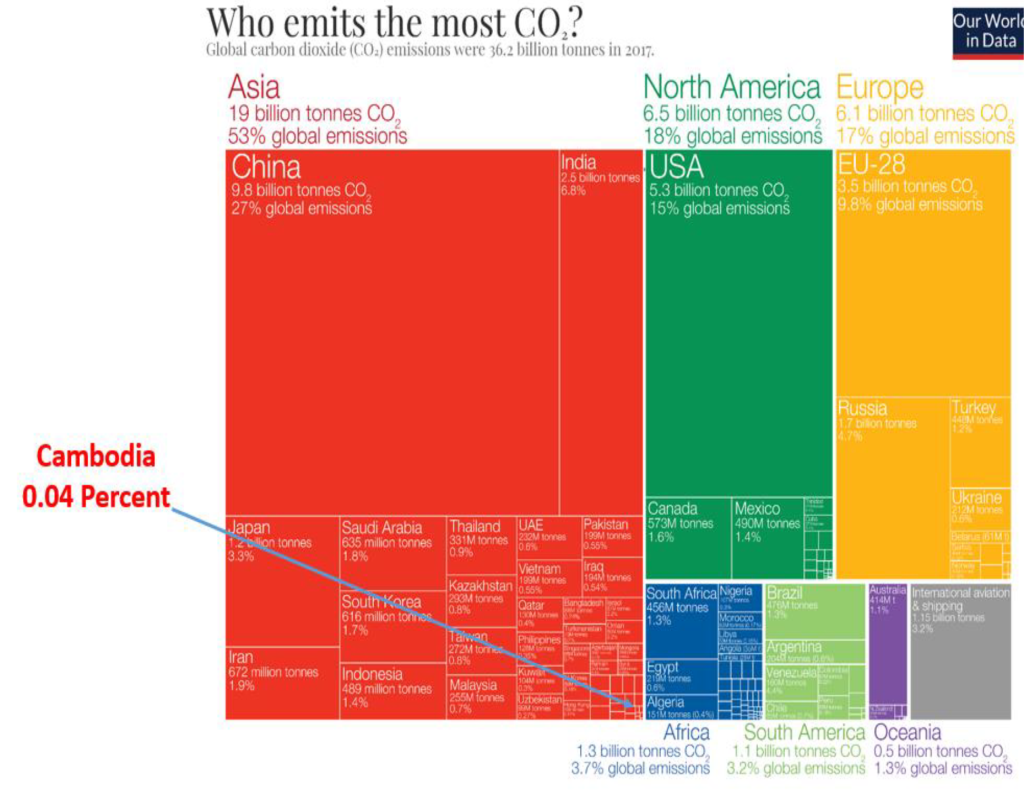

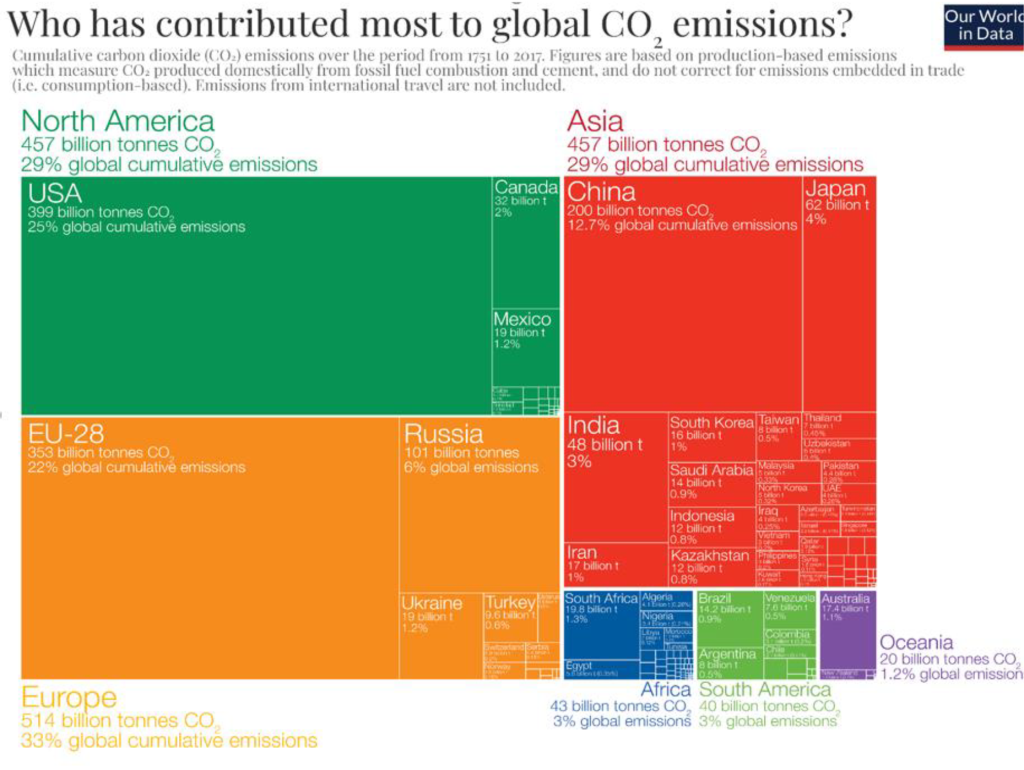

Clearly most developing countries have been bystanders in the causing climate change. The vast majority of emission that cause climate change come from the developed world, and from large developing countries such as India and China, the largest emitter of greenhouse gases (Figure 1). Cambodia only emits some 0.04 percent of total global emissions.

High income and middle income countries together make up some 51 percent of the population, but emit 86 percent of greenhouse gases. Low income countries, in contrast, have 9 percent of the population, but only emit 0.5 percent of total emissions. The average person in high income countries emits some 40 times the amount of CO2 that people in low income countries do.

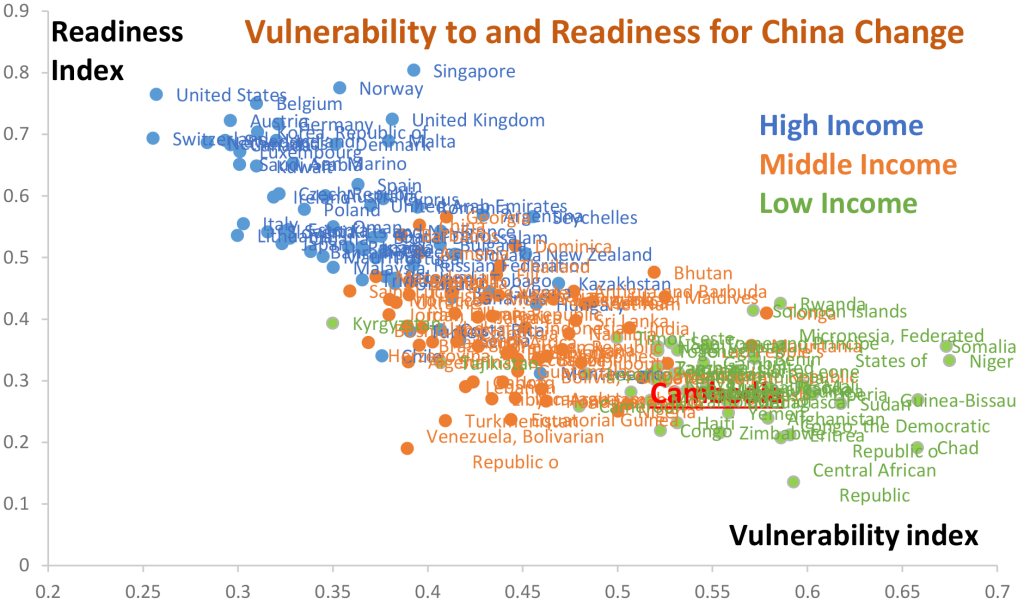

Moreover, history matters with greenhouse gases, as they stay around in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. If one were to consider historical emissions, the US and EU top the charts (Figure 2), but China is already number 3 on that scale, and is increasing its emissions and the share in the global accumulated emission because these are now falling in the EU and the US.

Cambodia’s share in the cumulative total is, again, negligible, at 0.014 percent of total emissions since the onset of the industrial revolution. Note that this excludes other sources of emission, including agriculture and land use change (e.g. deforestation) which in Cambodia (and other lower income countries) make up the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions.

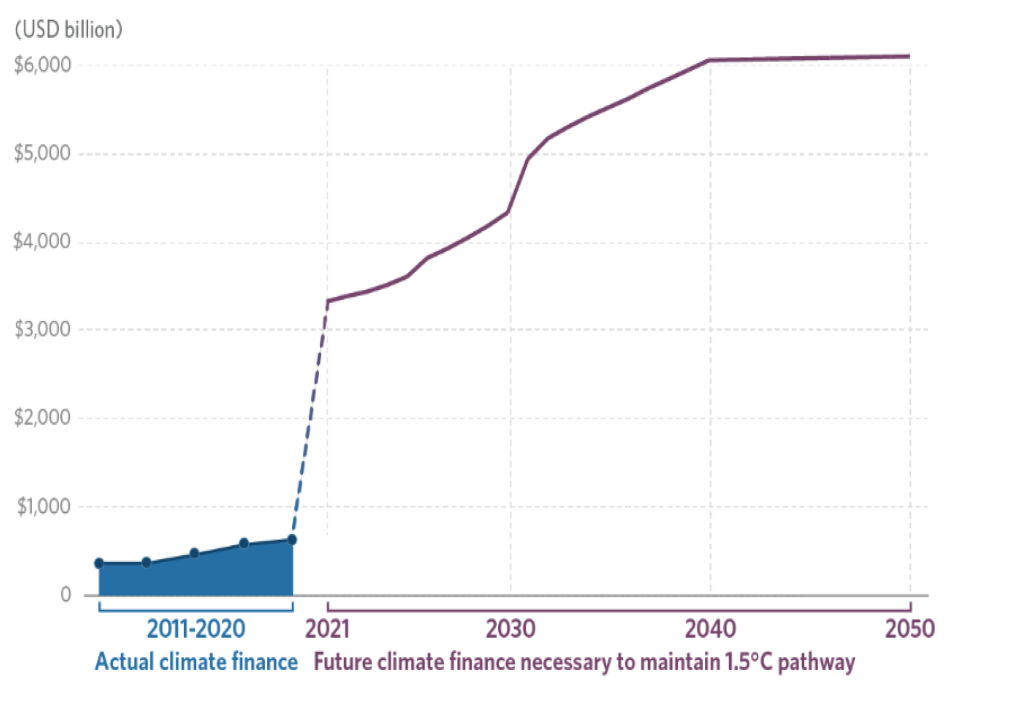

While most of greenhouse gas emissions come from higher income countries, it is lower income countries that are most vulnerable to their effects—including sea level rise and extreme weather events. Moreover, these countries are on average least prepared (Figure 3). Most will remember the recent floods in Pakistan, which put almost half of the country under water, or Tuvalu’s Simon Kofe speech at COP 26 standing in a suit and tie at a lectern set up in the sea draws attention to Tuvalu’s struggle against rising sea levels. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) released data showing that the number of people displaced by climate change-related disasters since 2010 has risen to 21.5 million. The Institute for Economy and Peace guestimates that this number could increase to 1.2 billion people by 2050, most of it in the developing world.

So who should take responsibility for reducing greenhouse gases?

One way to think about this is that rich countries need to massively decarbonize quickly – given their wealth and growth caused most of the problems, while developing countries can focus on development and take on board the innovations from development countries, and get paid for decarbonisation. The challenge is that much of the attention is focused on rich countries leveraging financing to offset emissions, or turn to “nature based solutions” largely in developing countries, which has been criticized for kind of incrementally undermines the direct behavioural change in rich countries. In addition, the EU is considering a carbon border adjustment mechanism. Many would consider this as injustice or some form of carbon colonialism.

But what is justice? In an ideal world, one could apply principles of justice such as the ones developed by philosopher John Rawls. In his seminal “A Theory of Justice” he imagined how an economic system would be designed if people were to decide on this without knowing their place in that world, but in which trade-offs between income equality and efficiency exist. Applying that principle to CO2 emissions, one could design a system of “rights” allocations for greenhouse gas emissions to individuals. The total rights would be based on what scientists tell us the earth could still absorb, either in current terms, or including historical emissions. People should get credit for innovations that reduce emissions, much like under the Kyoto protocol. Such an “equal rights” allocation would probably lead to massive transfers from (rich) pollution countries to (poor) clean countries.

In the real world, matters have taken a different turn. In the Kyoto protocol, the “equal but differential” responsibility for developing countries was recognized as a principle. The protocol established a “cap and trade” system of emissions in developed countries, with a mechanism to “buy” emission reductions in the developing world, the Clean Development Mechanism. However, since that did not restrict emissions from the largest developing countries, the scheme resulted into a transfer from the rich world to large, polluting developing countries. The largest polluter at the time, the United States, opted out. Total global emissions hardly changed trend during the lifetime of the protocol, but what it (and local policy innovations such as feed-in tariffs) did achieve was to catalyse innovations in renewable energy, which become increasingly competitive.

The 2015 Paris Agreement is more ambitious than the Kyoto protocol in that it requires all countries to make a contribution. The brilliance of the agreement is that it is up to the countries themselves to determine what they can do. This principle got every country in the world on board (again, except the US under the Trump administration), but the problem was that the Nationally Determined Contributions did not add up to what was needed to prevent catastrophic climate change. Since then, under the purview of the Agreement, many countries have gone further than what was pledged in Paris, and many now have a “zero net carbon” goal by 2050, or even 2040. China has a zero net carbon goal by 2060. The envisioned global carbon trading market, though, has not yet emerged, even though individual economies such as the EU and China have used this as a tool to achieve their goals. These goals also become more feasible as time—and technological innovation—progresses.

The Paris Agreement also paid attention to mitigation action, and established principles for finance. Developed countries committed to mobilise $100 billion a year in climate finance by 2020, and agreed to continue mobilising finance at this level until 2025. The funds were to be used for adaptation and mitigation, and were pledged in addition to the prevailing development assistance. The newly established Green Climate Fund was to be a key mechanism for achieving this.

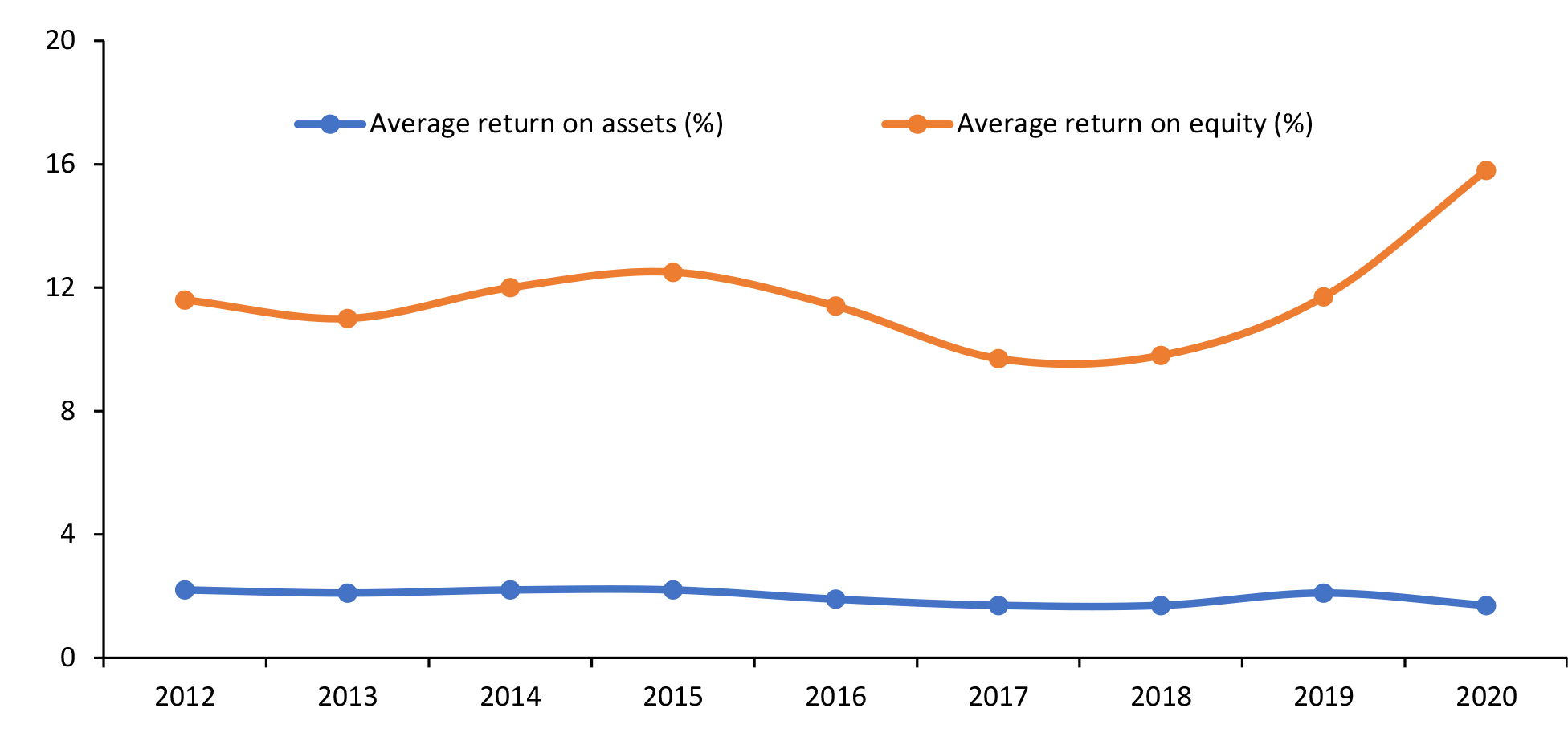

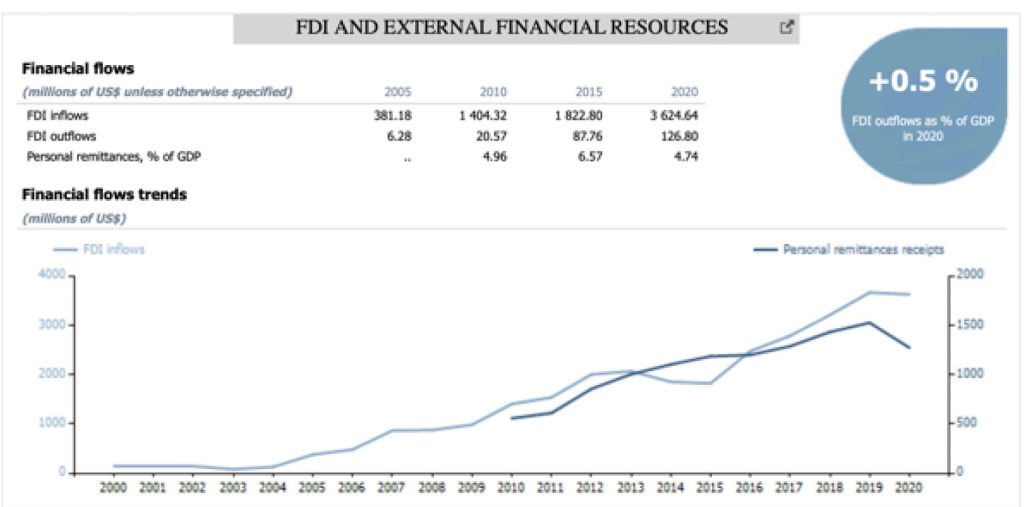

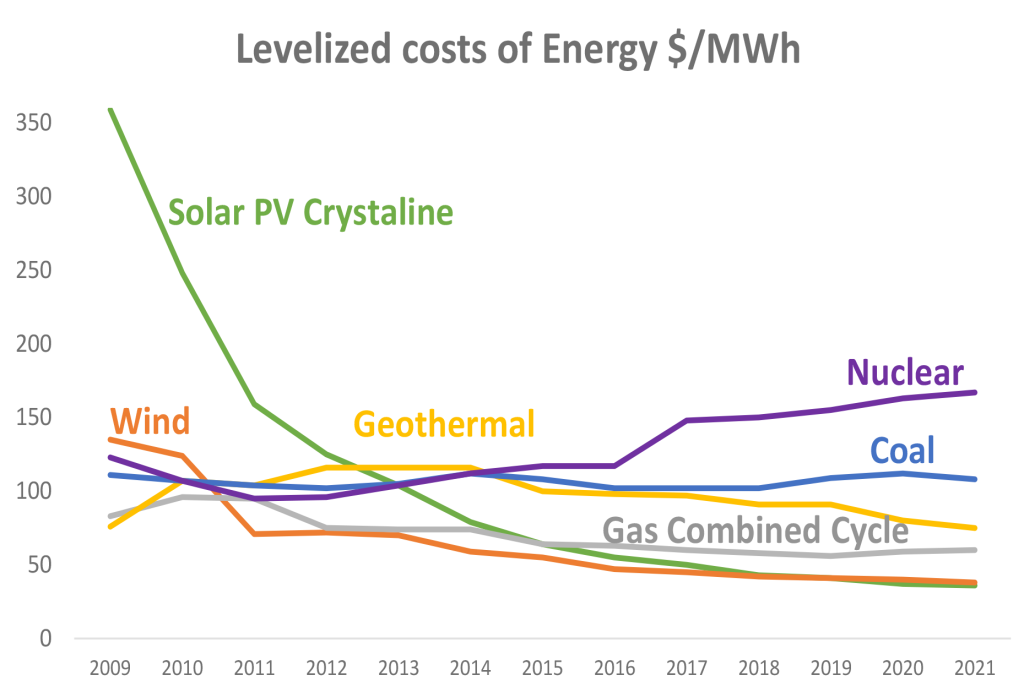

The picture on finance is a mixed one. Total Official Development Assistance (ODA) has grown since Paris, but only by some $29 billion—and spread out over multiple development goals, not just climate ones. The Green Climate Fund is still very modest in size, with total disbursements thus far of only $2.3 bn. in part due to the challenges the fund has had in establishing an effective governance mechanism. The picture of overall climate finance is more positive, though. The Climate Policy Initiative (Figure 4) estimates that total climate finance amounted to some USD632 in 2019/20 on average—a considerable amount, but still far from the USD 6 trillion the Initiative believes is needed annually. The vast majority of the funds went to mitigation, notably energy, and only 7 percent was allocated for adaptation. Most of the money went to projects in the developed world, and in East Asia and Pacific (China being the largest investor). Sub-saharan Africa only received USD19 bn. About half of the money came from private funding, again the majority of which was for funding renewable energy.

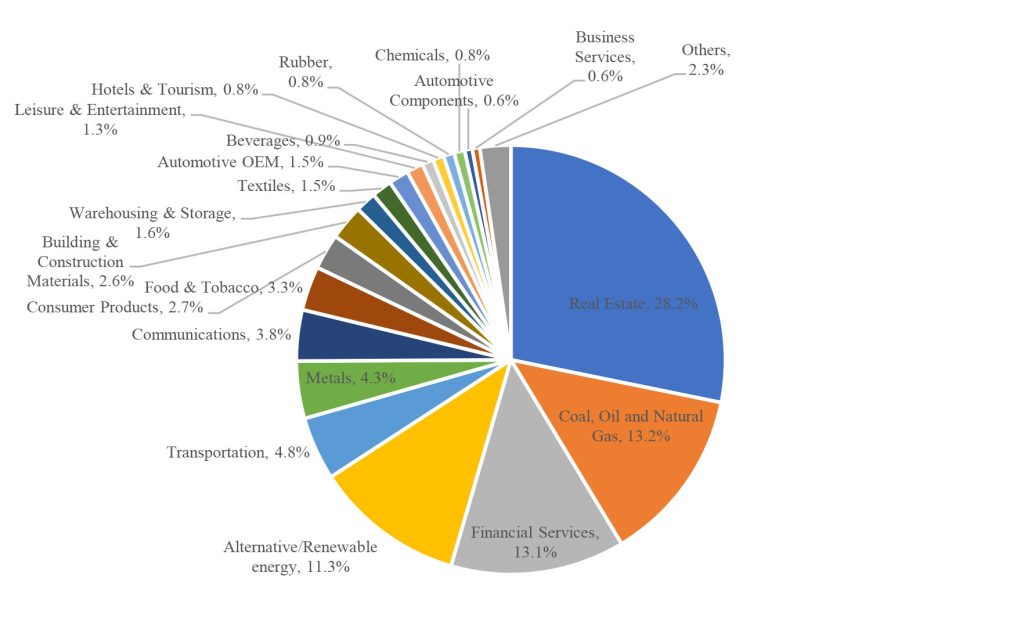

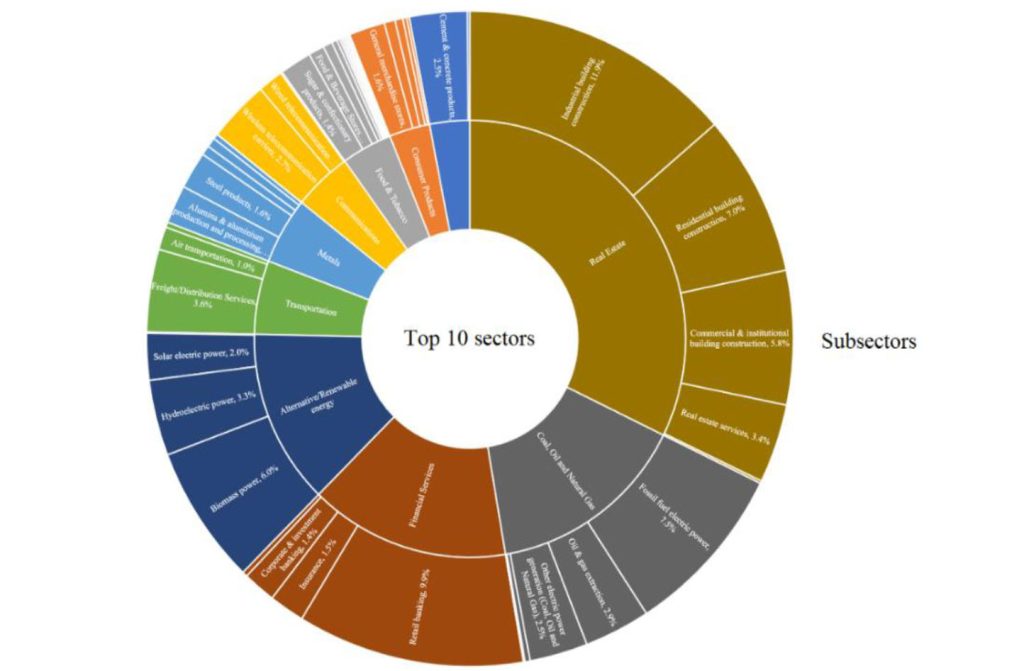

The drop in the costs of renewables has perhaps been the single most important effect of the focus on climate change in the past decades. Solar energy and wind are now cost competitive even without subsidies, and beat traditional sources such as coal, gas and nuclear (Figure 5). Electric vehicles are following a similar path, and clean hydrogen, which will remain needed for some applications, is on a learning curve that will make it competitive in the foreseeable future. The revolution in the costs of renewables has unleashed a large amount of private finance that is now available for it, and traditional fossil fuel power generation is rapidly becoming un-investable. China, which until recently was a large financier of coal fired power plants has pledged to phase out financing for fossil fuel power generation, following the path that multilateral development banks have already followed for the last decade. Today’s investment in fossil fuel risks becoming a stranded asset within the next decade.

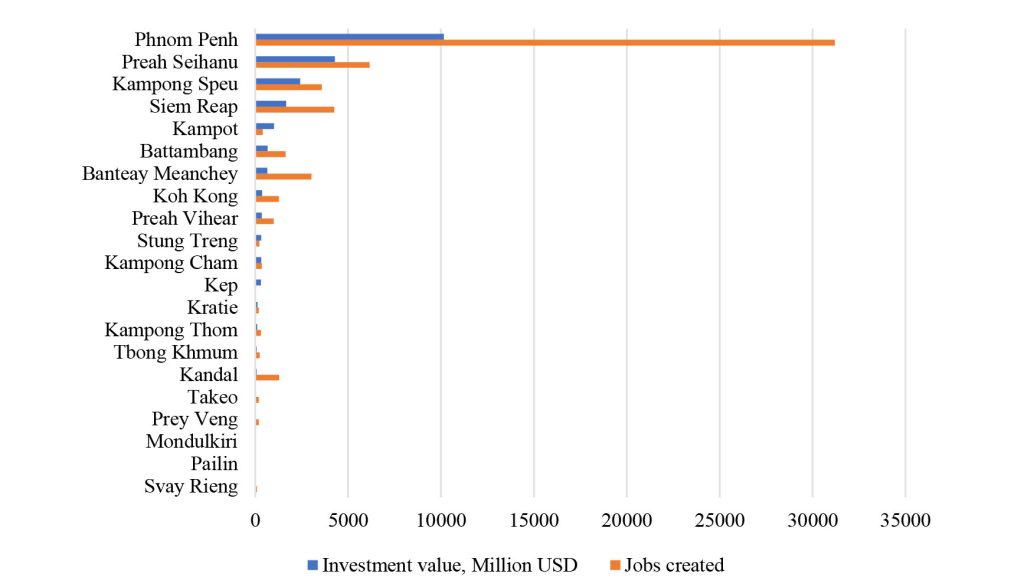

Cambodia as a signatory of the Paris Agreement has expressed its commitment to climate change mitigation and adaptation in its NDC. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 13) reconfirm this commitment. To match this commitment with development and poverty reduction, Cambodia can draw on private finance to develop a renewable energy sector that can provide the bulk of its need for the foreseeable future. Beyond price, renewables also have the advantage that they are more flexible, quicker to deploy, and more labour intensive than fossil fuels. Reliance on renewables also reduces the country’s vulnerability to price fluctuations on the international commodities market. Coal and gas are also a considerable source of local pollution—a major cause of death—and thus minimizing its use will have other benefits than energy costs. To attract more resources to renewable energy, rather than using domestic resources that could be used elsewhere, Cambodia’s broader investment climate is of critical importance.

For adaptation, as a low-middle income country, it should be able to draw on ODA sources of finance, and the key for that is to develop the clean and transparent administrative systems that allow donors to use these for aid money. Developing a strong pipeline of viable projects is also key, and investing in such a pipeline will pay off handsomely. In international fora, it can also continue to argue for more resources for adaptation, but even failing that, for a country that relies to a considerable extent on agriculture and tourism, investing in a resilient environment will have high economic, if not financial, returns. So even without aid, Cambodia can consider spending more.

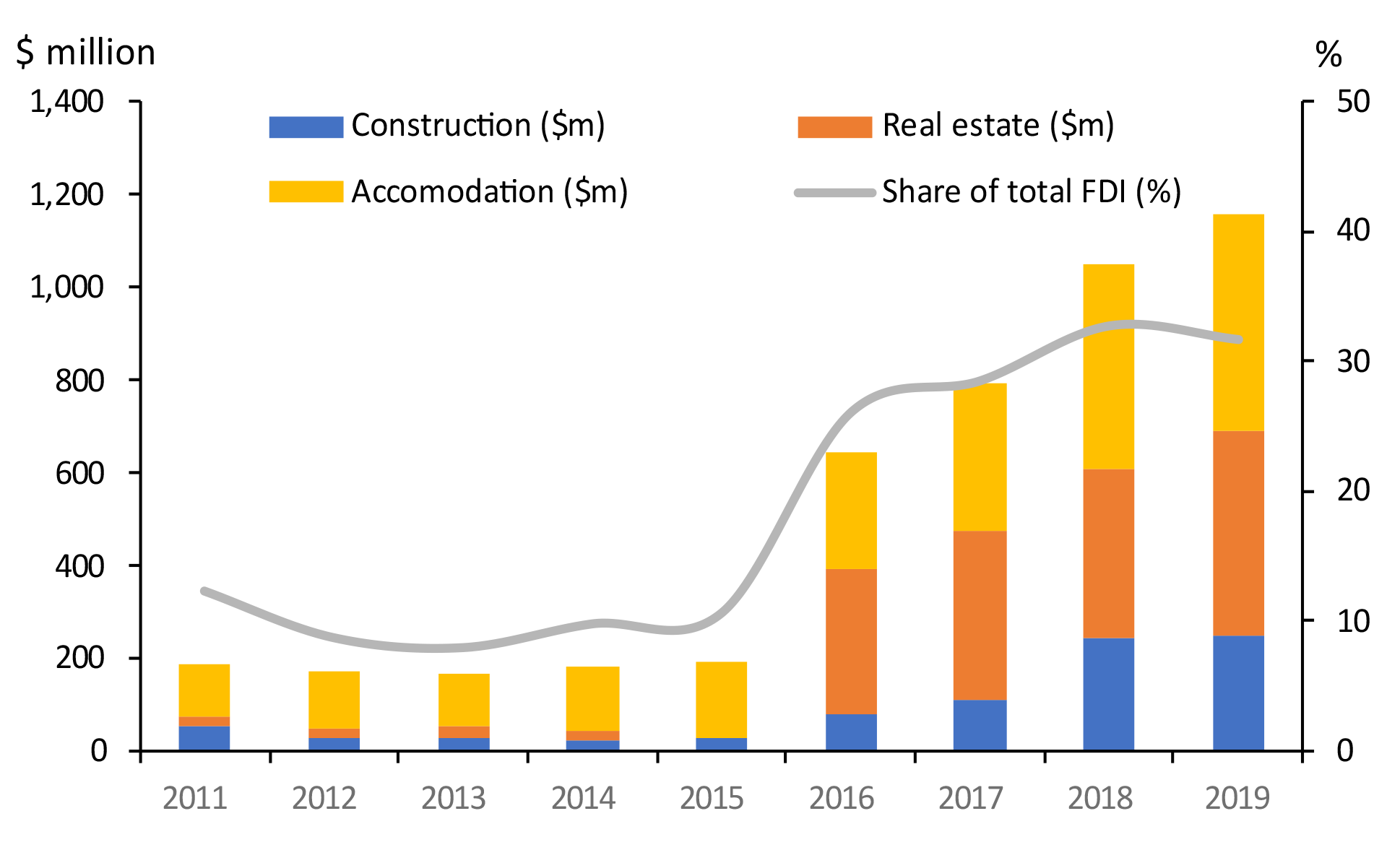

Figure 1

Cambodia’s share in global emissions is miniscule

Source: Our World in Data

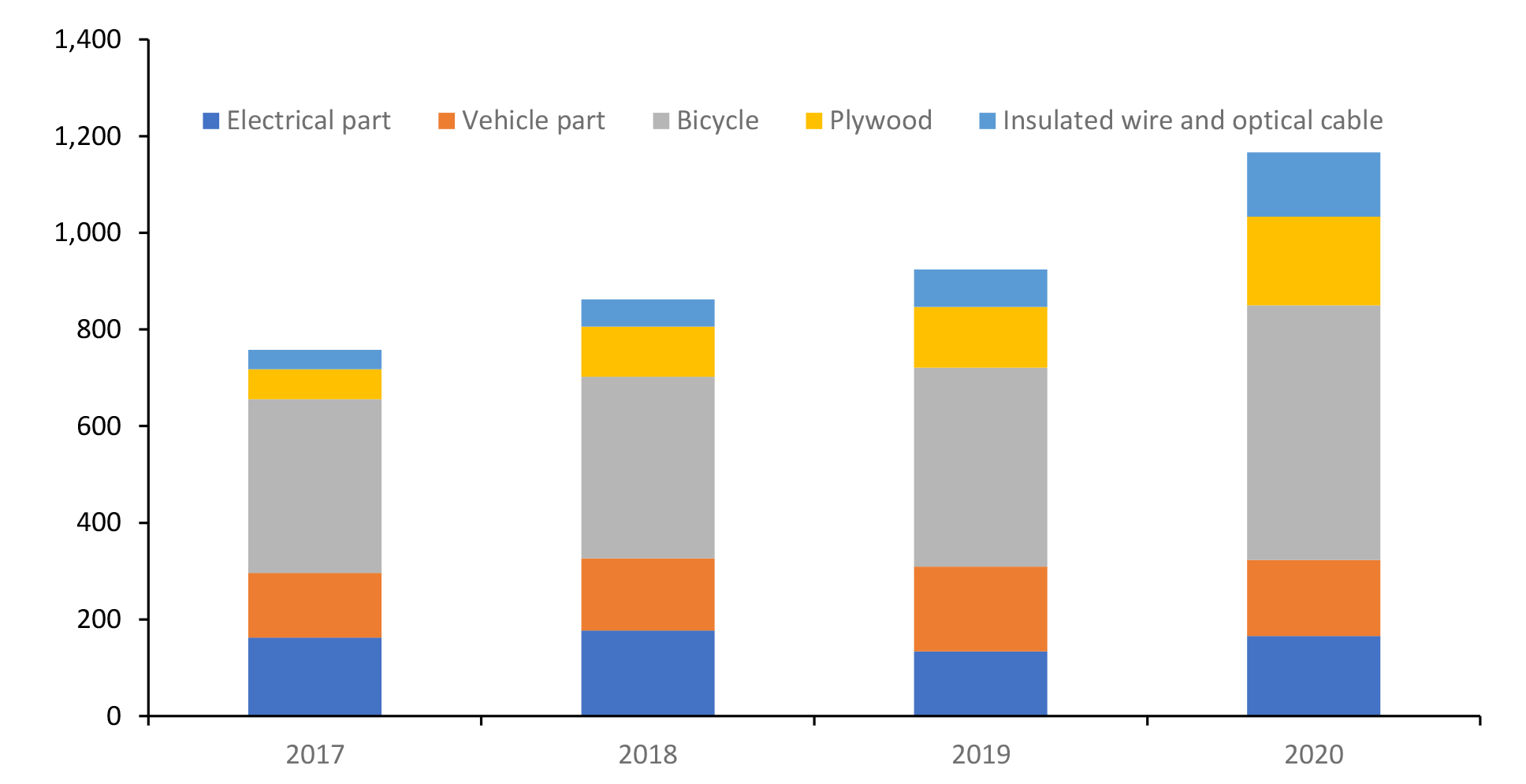

Figure 2

Historically, rich countries have contributed most

Source: Our World in Data

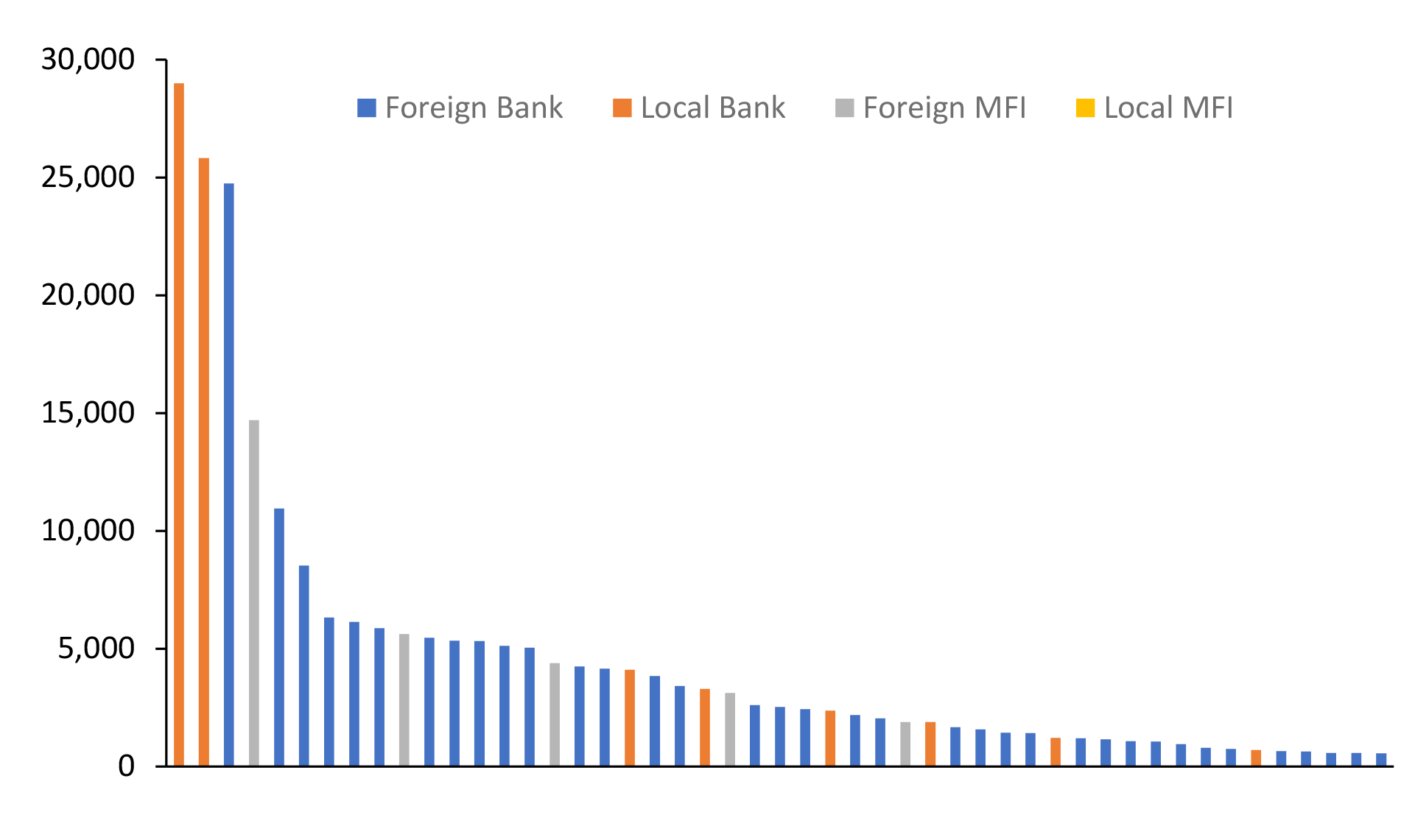

Figure 3

Poorer countries are most vulnerable and least prepared for climate change

Source: Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative

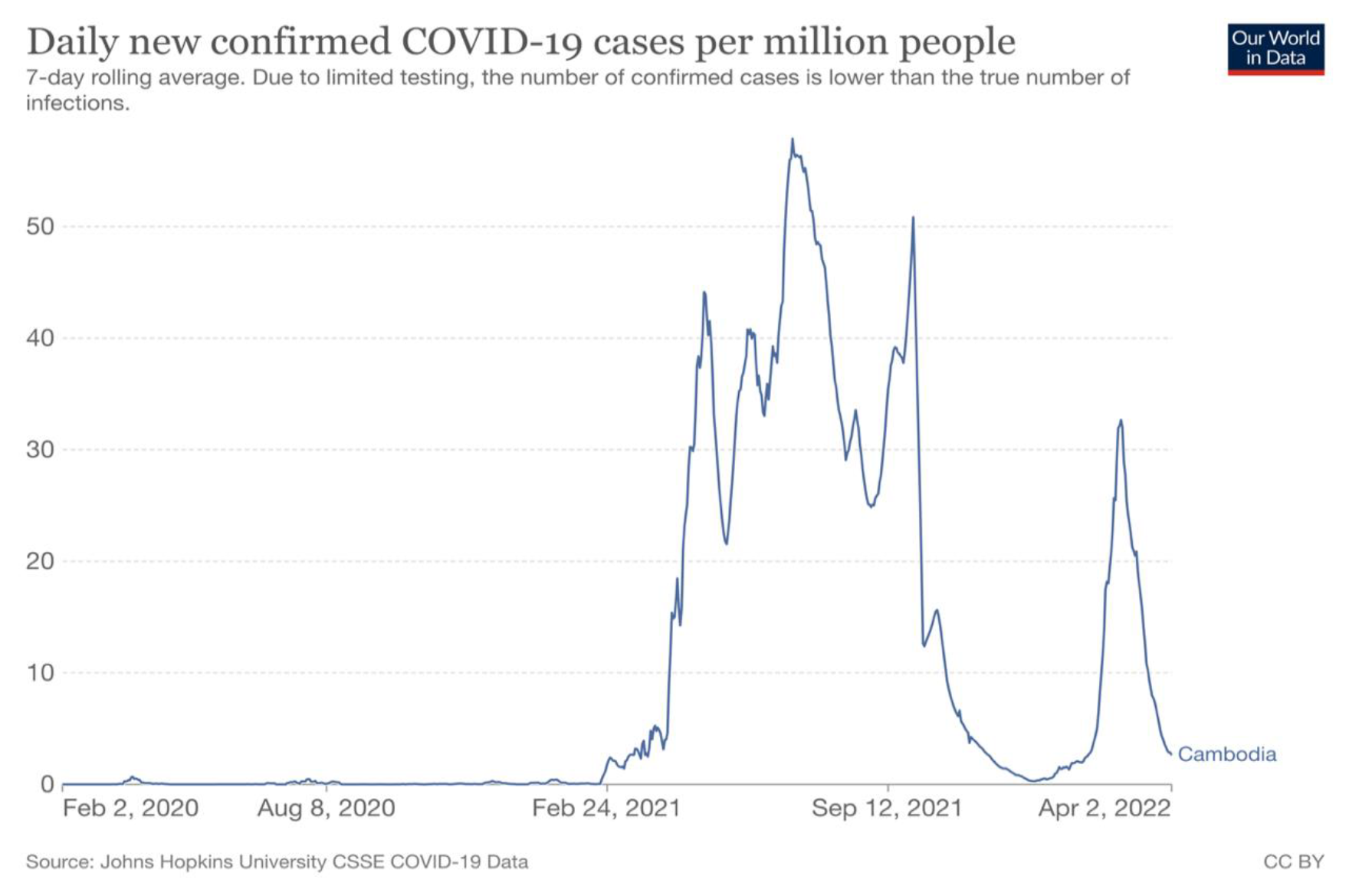

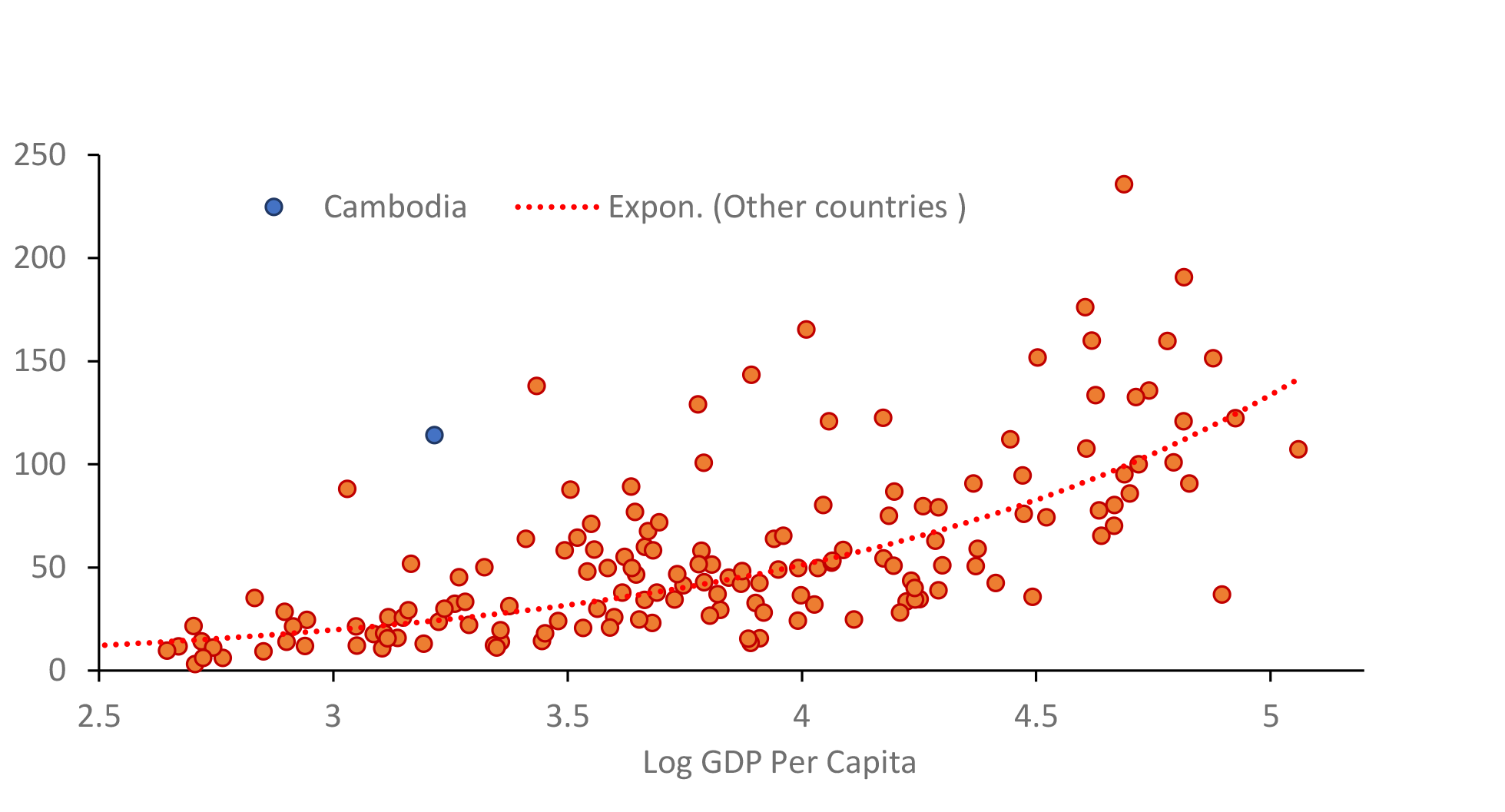

Figure 4

Climate finance is growing but is not nearly enough

Source: Climate Policy Initiative

Figure 5

Renewables are now more competitive than fossil fuels

Source: Lazard (2021) Lazard’s Levelised costs of energy version 15.0