Key messages

- The generation of benefits, externalities and sustainable linkages from inward FDI (IFDI) does not happen automatically, but requires the involvement and collaboration of all interested stakeholders (e.g. Chaminade & Vang, 2008; De Marchi et al., 2018).

- The impact of IFDI depends on the local embeddedness of multinational enterprises (MNEs), their linkages with local small and medium firms (SMEs), and the latter’s access to global vale chains (GVCs) that may allow for upgrading capabilities of domestic exporters (Comotti et al., 2020).

- The integration of IFDI into the local economy and industry structure needs be implemented with attention to sectoral and functional features of FDI and those of the (subnational) region/industry targeted (e.g. Crescenzi & Iammarino, 2017; Iammarino & McCann, 2013).

- The quality of FDI matters more than quantity in terms of overall impact on development and growth (e.g. Alfaro & Charlton, 2007), suggesting that FDI promotion policies should particularly target industries likely to supply inputs to domestic firms (Bajgar & Javorcik, 2020).

- Trade in GVCs and FDI are complementary phenomena that need be taken simultaneously into account when trying to capture the potential of internationalisation processes – and integration in global and macroregional GVCs – for local economic development (Rabellotti, 2003; Crescenzi et al., 2014; Iammarino, 2018; Gereffi et al., 2021).

- The interaction between global production networks and technological change is likely to produce unequal regional development, income polarization, low quality job, limited knowledge spillovers, infringement of environmental, human and social rights, etc.. Regulatory frameworks and clear governance of public intervention at supranational, national and local levels are key for sustainable development goals (e.g. Iammarino and McCann, 2013; Giuliani, 2016).

Structural change, diversification and IFDI trends in Cambodia

The case of Cambodia, as that of Vietnam in Southeast Asia, highlights relatively recent attempts to use IFDI attraction as a platform for export sophistication and sectoral diversification. As Yang (2019: 5) notes, over the last two decades Cambodia has undergone a process of rapid industrialisation and diversification, shifting from a contribution of the agriculture sector equal to 44% of GDP in 1998, to around 22% in 2019. The role of the garment sector increased from 17% to 22% of GDP over the same period, alongside other industries including food and beverage and light manufacturing; meanwhile the service sector with tourism maintaining its share of around 40% of GDP (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2019).

As Seila (2011: 31) notes, with a much less developed industrial base than neighbouring Thailand and Vietnam which initiated earlier their transitions, in Cambodia FDI policy support – without local content requirements or compulsory joint ventures – spurred a ‘crowding in’ effect for the garment and textiles industry. Both tourism and the export-oriented garment sector have been critical to the country’s economic transformation (Slocomb, 2010; Philippsen, 2021). Yang (2019) also highlights the role that FDI played as Cambodia’s export structure also gradually upgraded and diversified – with the top 10 products exported from 2001 to 2018 improving in both sophistication and quality, shifting partially from low-tech to medium-tech and strengthening integration in regional and global GVCs (Obashi, 2022; Observatory of Economic Complexity). Further, the service sector grew on average 8.3% over the last 15 years, with tourism, financial services, real estate, ICT, postal services, transport, and logistics collectively being the biggest contributors to the economy; among them some (e.g. real estate and finance) are also the largest FDI attractors.

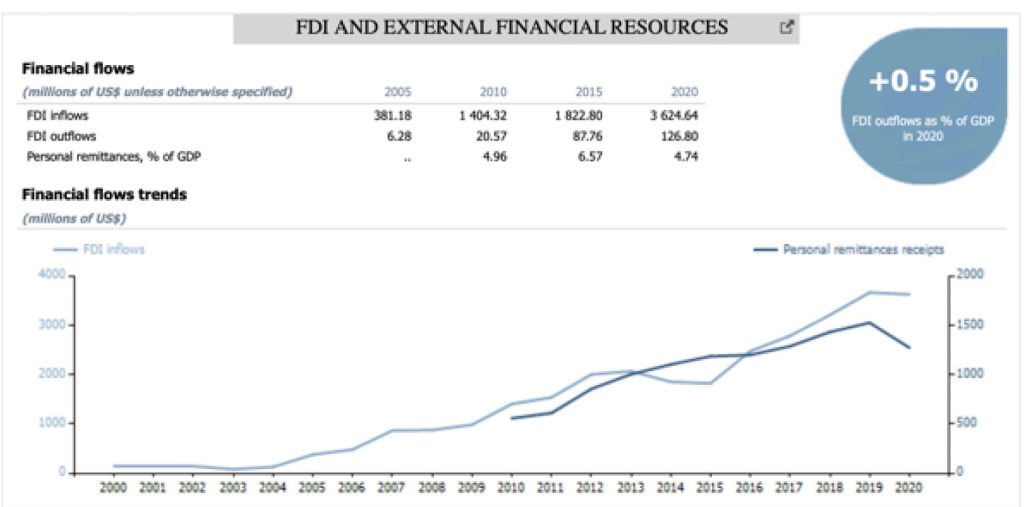

IFDI in Cambodia rose from USD 381.18 million in 2005 to USD 3,624.64 million in 2020, with FDI outflows over the same period also rising from USD 6.28 million to USD 126.80 million (UNCTAD, 2021). UNCTAD data suggests a general upward trend in IFDI, with substantial rises in the level of inflows between 2004 and 2012, and again between 2015 and 2019.

Figure 1. FDI trends in Cambodia (Source: UNCTAD, 2021)

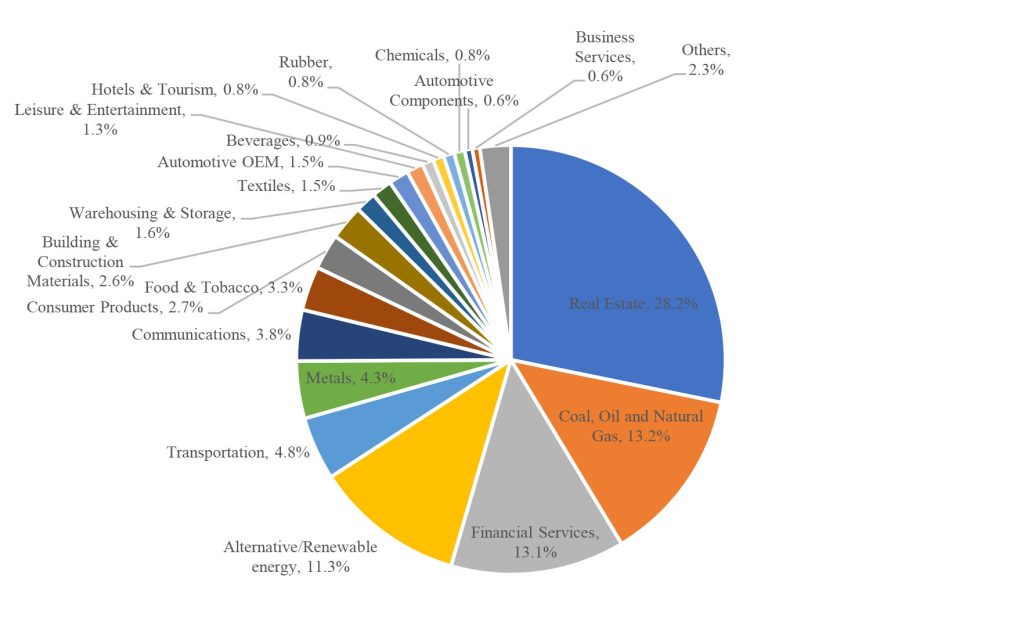

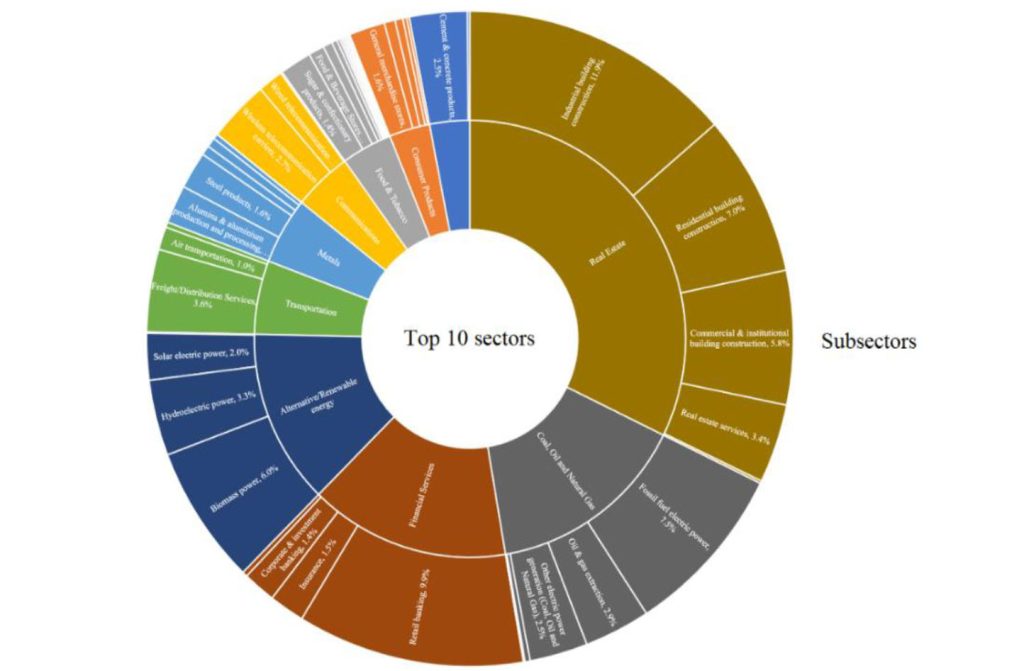

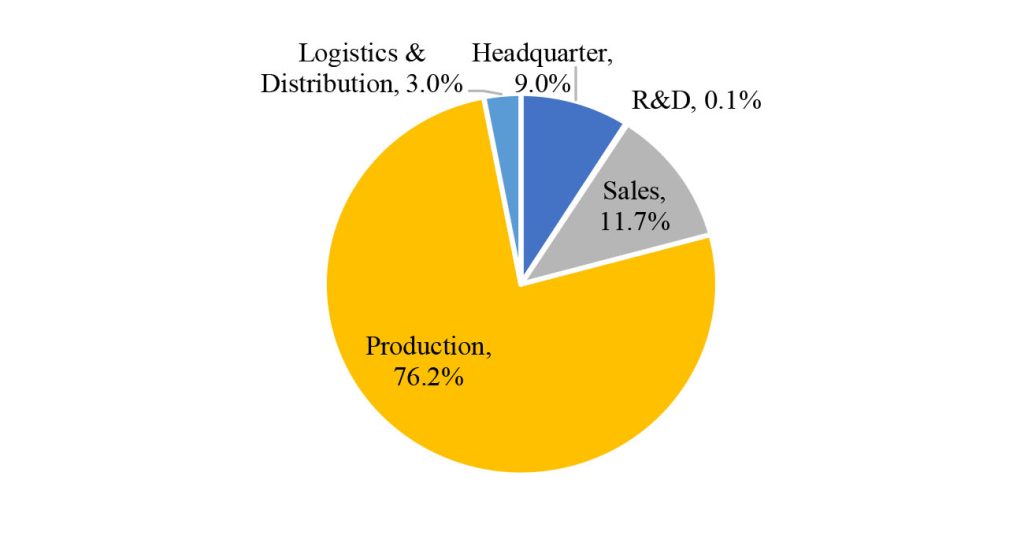

fDiMarket database (see Appendix at the end of this document) consistently show that between 2003 and 2017 Cambodia greenfield IFDI grew significantly, with a sharp increase particularly in 2007-2008. Sectors such as Real estate, Coal, Oil and Natural Gas, and Financial Services attracted the highest value of FDI, while others with low investment values – especially Textiles, Consumer Goods and Food & Tobacco – generated large numbers of jobs (Chart A.1). FDI inflows are also highly concentrated in specific sub-sectors: for example, Retail banking in Financial Services, Fossil fuel electric power in Coal, Oil and Natural Gas, Biomass power in Alternative/Renewable Energy, and Freight/Distribution Services in Transportation. IFDI in the largest sector, Real Estate, is distributed relatively evenly across sub-sectors. Looking at function or GVC stage of IFDI, there was no significant change during 2003-2017: investments in production accounts for over 75% of the total, whilst IFDI in R&D functions represents still a tiny share (Chart A.3).

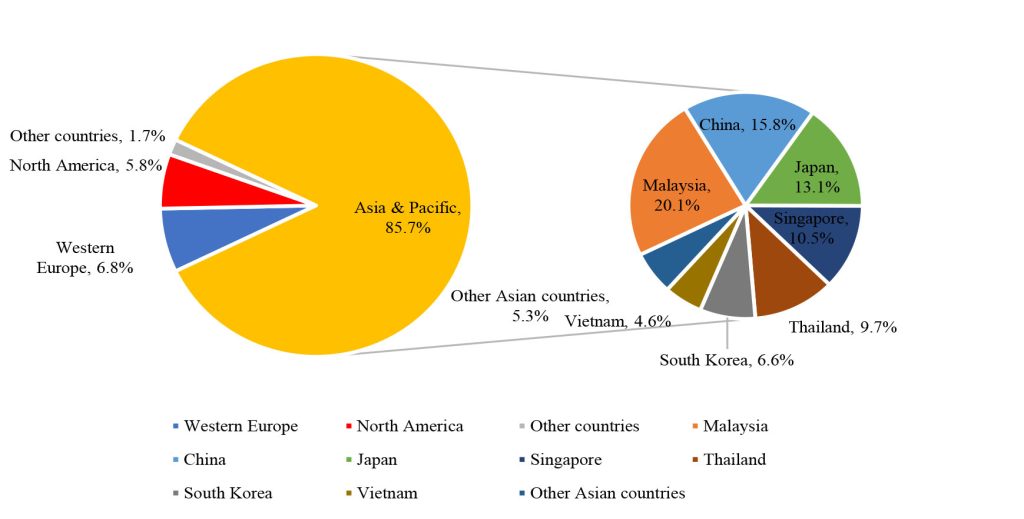

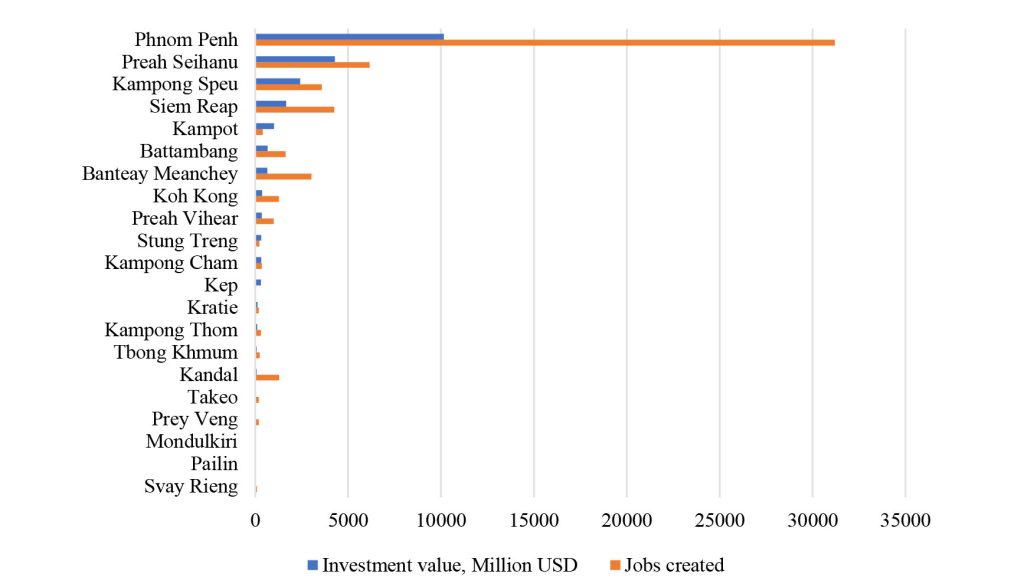

Turning to the geography of origin of IFDI in Cambodia during the period considered, 75 % came from the Asia & Pacific area, within which Malaysia, China, Japan and Thailand accounted for the highest shares. This is a confirmation of the strong integration of Cambodia into macroregional GVCs. On the other hand, some IFDI also originated from economic hotspots in both the European Union and the US (Chart A.4). In terms of subnational distribution within Cambodia, as expected the capital region Phnom Penh received the largest greenfield FDI inflows, both in terms of amount invested and jobs creation (Chart A.5).

FDI Policies: Tax Incentives, Key Actors and Regulations

Cambodia’s tax regime and trade policies have been evolving since the mid-1990s. The current tax regime was finalised as part of Investment Law of Cambodia of 2003, entitling investors to incentives including: “[…] profit tax exemption or use of special depreciation and duty-free import of production equipment, construction materials, raw materials, intermediate goods, and accessories for export-oriented investment projects. The tax exemption period is composed of a trigger period plus additional 3 years and a priority period (determined by the Financial Management Law)” (Chheang, 2017: 3). Although there is a variety of sectors that do not qualify for tax incentives – e.g., commercial retail and wholesale, transport (except in railways), restaurants, financial service, media, forestry, tourism, real estate – Cambodian Special Economic Zones (SEZs) operate under different rules where FDI tax incentives may be provided.

Tjia et al.’s (2021: 25-27) Report – part of the ‘Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones Along Belt and Road Workshop Series’ – summarises the current tax regime for FDI in Cambodia. It highlights three main types of incentives available to foreign investors: a minimum tax exception, corporate income tax exemption, and special tax rate, alongside exceptions on import duties. Specific rules on taxes and their application for foreign investors are also highlighted in the document, as are rules and exemptions applicable to the case of SEZs which have a separate operational and tax status to that of other types of FDI.

In terms of actors, the OECD’s (2018) Investment Policy Reviews: Cambodia summarises some of the significant features of the Cambodian FDI model. First, the crucial role of Cambodia investment promotion agency – the Council for Development of Cambodia (CDC) – created when the country’s first Investment Law was promulgated in 1994 and tasked with managing FDI inflows. Though its core mandate has remained constant over time, its governance has radically shifted over the last twenty years, and now is directly accountable the Council of Ministers and acts both by shaping investment strategies as well as by accepting/rejecting investment proposals. Currently framed by Cambodia’s Industrial Development Policy 2015-25 (CDC, 2015), this highlights the various roles of the CDC in setting direction, monitoring progress, and working closely with the Committee for Economic and Financial Policy and the Steering Committee for Private Sector Development to implement the policy as a high level and strategic body within the Cambodian government.

Tjia et al.’s (2021) review also adds specific details on the CDC and other governance elements. First, it recognises that the CDC is the ‘highest decision-making body for private and public investment’ in Cambodia (CDC, 2017). At the same time, it also highlights the role of other two institutions: the Cambodia Investment Board (CIB) and the Cambodian Special Economic Zone Board (CSEZB). While the CDC deals with FDI related matters, it is the Ministry of Commerce that exercises general policy oversight over all other business activities.

Within the Cambodia’s investment framework there are three types of FDI projects allowed in the country: either general business, concessions business, or business related to SEZ. While the first simply requires general approval, the second and third require specific permissions to use state property and to allow for construction of infrastructure, etc. All sectors of the Cambodian economy are open to FDI, though there are regulations banning activities deemed harmful to the environment, health, or health culture, as well as land ownership (Chheang, 2017; OECD, 2018).

Main Messages for Policy Discussion

- Cambodia represents an interesting case of a relatively successful economic transformation with evident economic gains linked to FDI attraction strategies and integration in regional GVCs, following neighbouring examples.

- Despite its still ongoing development challenges – and considering the difficulties in the aftermath of the Covid-19 shock and recent commercial and military wars – Cambodia has so far been able to use FDI to partially upgrade, diversify and increase sophistication of its exports, catching up in the process with neighbours, even though it started international integration much later.

- Tourism and export-oriented garment industries were critical to the country’s economic transformation away from agriculture. From the 2000s, a process of diversification from garment to light manufacturing and, particularly, services, has unfolded.

- A fundamental role was played by the regional ‘big player’ China since the early 2000s, with later Chinese OFDI and participation in the ‘Belt and Road’ scheme.

- Cambodia shows strong integration in the macro-regional trade and GVC networks, joining ASEAN in 1999 as the 10th member, and subsequently establishing numerous multilateral and bilateral trade agreements.

- Carefully designed incentives for FDI have been put in place over time, e.g. tax exemptions fixed periods, sectoral exclusions to promote the local ecosystem and industrial base, SEZs operating under different rules, bans to activities deemed harmful, etc.; they helped overcoming some needed protectionist measures (e.g. MFN higher than in the area). However, more ad hoc measures of FDI support, particularly sector specific regulations, could be learnt by screening international experiences: e.g. Eco-tourism, Extraction Codes, special support to attract FDI projects with significant socio-economic impact.

- Beyond tax and incentives policies, Cambodia is distinguished by its clear governance and framework for FDI decision-making, led by the CDC which was able to transform and update gradually over time to the changes in the global competitive environment.

- However, ongoing risk assessment is necessary as IFDI may be associated to limited knowledge spillovers on domestic firms, tax loopholes, increasing gaps in tax incentives and public support between foreign and domestic firms (curbing the development of local production systems), and predatory attitudes and violation of workers and environmental rights by MNEs.

- As it emerges clearly from the Appendix, and alike trade, IFDI is concentrated in relatively low value-added sectors, mostly in the production stages of GVCs (IFDI in R&D is almost null), and at the subnational level, as the bulk of investment is directed to the Phnom Penh. Thus, articulating internationalization policies at both sectoral and provincial level to avert FDI concentration is paramount.

- While diversity of industry and exports have increased as a result of FDI attraction, concerns remain over development traps preventing the shift to higher productivity and value-added activities. In addition, globalization through trade, FDI, participation in GVCs, etc. brings about income polarization and increasing inequality at both individual and geographical level. Thus, support to internationalization needs to consider synergies with areas such as STI policy and skill upgrading, social policies and governance for public investment, and regulations for clear sustainable standards at national and local level.

References

- Alfaro, L., and Charlton, A., 2007. Growth and the Quality of Foreign Direct Investment: Is All FDI Equal?. Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

- Bajgar, M., and Javorcik, B., 2020. Climbing the rungs of the quality ladder: FDI and domestic exporters in Romania. The Economic Journal, 130(628), pp.937-955.

- CDC. 2015. Cambodia Industrial Development Policy 2015 – 2025

- CDC. 2017. Who We Are, [Last accessed; 09/02/2022]

- Chaminade, C., and Vang, J., 2008. Upgrading in Asian clusters: Rethinking the importance of interactive learning. Science, Technology and Society, 13(1), pp.61-94.

Chheang, V., 2017. FDI, services liberalization and logistics development in Cambodia. In Services liberalization in ASEAN: Foreign direct investment in logistics. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, pp.268-297. - Comotti, S., Crescenzi, R. and Iammarino, S. (2020), “Foreign direct investment, global value chains and regional economic development in Europe”, European Commission, DG Regio, Contract no. 2018CE160AT082:

- Crescenzi, R., and Iammarino, S., 2017. Global investments and regional development trajectories: the missing links. Regional Studies, 51(1), pp.97-115.

Crescenzi, R., Pietrobelli, C., and Rabellotti, R., (2014). Innovation drivers, value chains and the geography of multinational corporations in Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 14(6), pp.1053-1086. - De Marchi, V., Giuliani, E. and Rabellotti, R., 2018. Do global value chains offer developing countries learning and innovation opportunities? The European Journal of Development Research, 30(3), 389-407.

- Gereffi, G., Lim, H.C., and Lee, J., (2021). Trade policies, firm strategies, and adaptive reconfigurations of global value chains. Journal of International Business Policy, 4(4), pp.506-522.

- Giuliani, E. (2016). Human rights and corporate social responsibility in developing countries’ industrial clusters. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(1), 39-54.

- Iammarino, S., 2018. FDI and regional development policy. Journal of International Business Policy, 1(3), pp.157-183.

- Iammarino, S., and McCann, P., 2013. Multinationals and economic geography: Location, technology and innovation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ministry of Economy and Finance, Cambodia. 2019. Development of Cambodia’s Macroeconomics: 25-year Evolution, [Last accessed: 09/02/2022, Available at: https://www.mef.gov.kh/must-see-documents.html]

- Obashi, A., 2022. Overview of Foreign Direct Investment, Trade, and Global Value Chains in East Asia, ERIA Discussion Paper Series, 147, pp.1-44.

- OECD. 2018. OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Cambodia, [Last accessed: 09/02/2022]

- O’Neill, D., 2014. Playing risk: Chinese foreign direct investment in Cambodia. Contemporary Southeast Asia, pp.173-205.

- Philippsen, L.M., 2021. Cambodia: The Pursuit of Sustainable Economic Development. Genuine Savings 1970-2019. Master’s Thesis, Lund University: Lund, Sweden.

- Rabellotti, R., 2003. The Rise and Fall of the Furniture Cluster of Chipilo, Puebla, Mexico. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo.

- Seila, N.E.T., 2011. Economic Growth in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand: Has FDI Really Played an Important Role? Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications. ANDA Discussion Paper, 74, pp.1-38.

- Slocomb, M., 2010. An Economic History of Cambodia in the twentieth century, National University of Singapore Press: Singapore.

- Tjia, L.Y., Chung, J., Yao, C., and Li, L.C., 2021. Training Pack Cambodia, Research Centre for Sustainable Hong Kong City University of Hong Kong, [Last accessed: 09/02/22]

- UNCTAD. 2021. General Profile: Cambodia, [Last accessed: 09/02/2022]

- Yang, M., 2019. FDI as a driver of Cambodia’s export sophistication and diversification, [Last accessed: 09/02/2022]

Appendix – Inward FDI in Cambodia, 2003-2017 (fDimarkets Data)

A more nuanced picture of greenfield IFDI trends in Cambodia, with focus on sector, function, geography of origin and of subnational destination can be extracted from fDiMarkets, a database created and maintained by the Financial Times, covering cross-border greenfield investments for all countries and sectors worldwide between 2003 and 2017. The accuracy of fDiMarkets and its coherence with official statistical sources has been tested and confirmed by a consolidated literature (see Crescenzi et al., 2014 and Comotti et al., 2020).

Chart A.1. IFDI value, % shares top 20 sectors, 2003-2017

Chart A.2. IFDI value, sub-sectors of the top 10 sectors, 2003-2017

Chart A.3. Share of IFDI value by function/GVC stage, 2003-2017

Chart A.4. Share of IFDI value by macro-region and country of origin, 2003-2017

Chart A.5. IFDI subnational distribution, value and job created by province, 2003-2017

Note: the destination of ‘other investments’ (31368.28 million USD, 26.59% of total) could not be located at provincial level, thus it is excluded from the above.