Key Messages

- Two years after the pandemic, Cambodia lead ASEAN in moving rapidly to re-open its economy. An impressive vaccination campaign and pragmatic economic policies have helped position the country for economic recovery.

- However, risks remain and three key challenges must be addressed to support recovery and long-term growth.

- The first challenge relates to maintaining health security and the need to strengthen the healthcare system. Had there been more healthcare capacity, a more targeted approach in managing the outbreak would have been feasible, reducing the toll on the economy and livelihoods.

- Second is supporting new sources of growth. With the construction and real estate boom ending, future growth must come from diversification within agriculture and manufacturing, with a move towards higher value-added activities. A revival in tourism will aid recovery but will need to cater to higher-spending tourists.

- The last challenge relates to managing financial sector risks. The forbearance measures related to the pandemic and growth slowdown has increased indebtedness of banks and households. While a gradual winding back may avert a financial meltdown, increased regulation and supervision is required for long term financial sustainability.

Introduction

Cambodia was one of the first countries in Asia to record a case of COVID-19 and was also heavily impacted by the pandemic. Two years later, it was the first country in ASEAN to move ahead with re-opening unilaterally. An impressive vaccination campaign and pragmatic economic policies have helped position the country for economic recovery. However, risks remain. This blog summarizes developments in 2020-2021 and highlights three key issues in support of recovery and long-term growth.

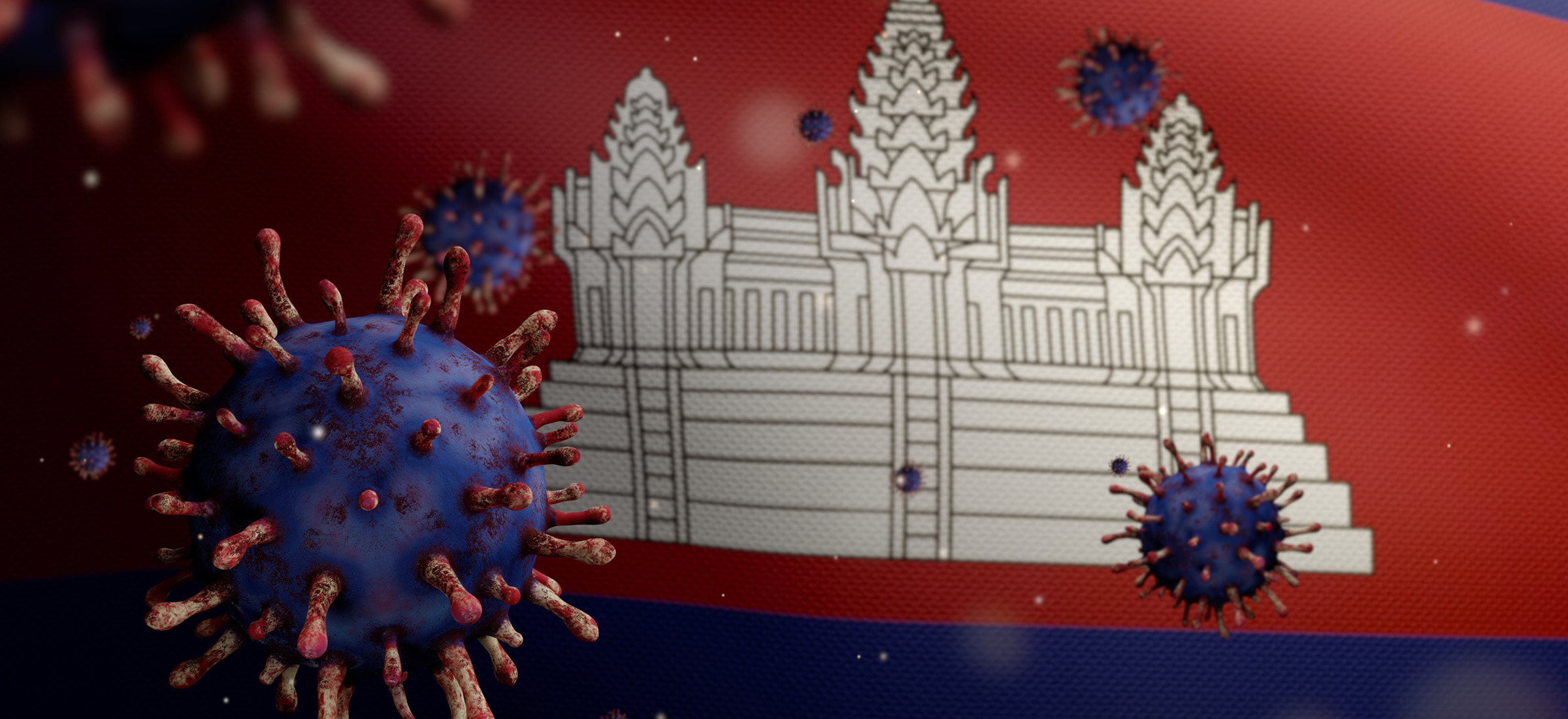

Strict border controls helped Cambodia avoid widespread transmission of COVID-19 during 2020, but this changed in February 2021 with a major outbreak in Phnom Penh. The disease quickly spread to all provinces of the country, triggering school closures, lockdowns, and other measures to slow transmission of the virus. For most of 2021, Cambodia was in a race between the vaccine and the virus. Vaccination began in January 2021 with donations of Sinopharm vaccines from China, and accelerated through the year as the government leveraged bilateral ties to secure additional vaccine supplies. Clear public communication, a rapid expansion of vaccination to include younger children, and a pragmatic area-based approach to vaccine rollout all contributed to an exceptionally quick vaccine rollout.

Cambodia recorded its first case of the Omicron variant in December 2021. This new variant spread rapidly with the 7-day moving average reached 550 cases in late February 2022 before a change in testing protocols brought reported case numbers down. Despite this threat, economic activity continued to recover. Mobility, which is a good short-term proxy for economic activity, had largely returned to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2021 and has not been severely impacted by the spread of Omicron. Flight connectivity and international visitor arrivals also started to improve, albeit from a low base. All remaining protocols affecting international visitors were removed in October 2022.

These developments have positioned the economy for recovery in 2022, with the IMF forecasting growth of 5.1 per cent for the year in its World Economic Outlook (IMF, 2021a) and keeping this forecast relatively unchanged at 5 per cent following its Article IV Consultation concluded in September 2022 (IMF 2022). This is promising given a gloomy global outlook and following a contraction of 3.1 per cent in 2020 and modest growth of 2.1 per cent in 2021 (IMF, 2021a). This return to growth is encouraging, but the recovery remains fragile beyond just the uncertain global inflation and growth outlook. In 2022 and beyond, policy makers will need to address three key challenges to safeguard the recovery: (i) maintaining health security; (ii) supporting new sources of growth; and (iii) managing financial sector risks.

Challenge No. 1 – Improving health surveillance and healthcare capacity

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is not yet over, it is clear that poor countries in particular need to be better prepared for future health and related crises, which are likely to become more frequent.

Cambodia recorded its sharpest daily decline of COVID-19 cases when they fell from 978 on 30 September to 232 on 1 October 2021 (Figure 1). The overnight reduction of 76 per cent was due to a change in the approach taken on testing. By eliminating random testing of asymptomatic individuals, the reported numbers now only reflected cases presented for testing following the onset of symptoms.

With the sharp drop in testing, case numbers remained predictably low for some time, leading to the easing of lockdowns and the opening of borders in November 2021. At the time, there were concerns that this approach to ending the pandemic would prove to be illusionary rather than visionary. It is now clear that this was indeed the right approach, and reduced the burden on the economy, and especially the poor, by facilitating an earlier and stronger recovery.

Figure 1

As noted, Cambodia’s record on vaccinations has been remarkable. The vaccination rate in February 2022 at above 80 per cent of its population is one of the world’s highest with the WHO reporting that 99.0% of all adults have received two vaccine doses (WHO, 2022a). The government has also been proactive in expanding vaccine coverage to children and offering booster doses from different manufacturers to increase immune response. As a result, over 80 per cent of the population were fully vaccinated by March 2022, and population-level immunity continues to improve.

Although adequate supplies of vaccines from China and other partners were important in the vaccination outcome, Cambodia deserves credit for managing the logistics efficiently, enabling a rapid rollout under challenging circumstances. Work to strengthen vaccine supply chains has continued and the government has expanded its cold-chain infrastructure to enable nationwide rollout of mRNA vaccines for booster doses and vaccination of young children.

Despite these ongoing investments, Cambodia’s health system capacity remains among the lowest in Asia. For instance, there are currently only 0.7 hospital beds per 1,000 people, compared to 2.6 in Vietnam and an average 4.7 amongst the OECD countries. This suggests that a future surge in cases of a new COVID-19 variant requiring hospitalisation could quickly overwhelm the healthcare system.

The key lesson from the pandemic is the need to increase both the quality and availability of health services. Cambodia had been falling behind on many of its Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) before the pandemic (see Sachs et al, 2021), leaving it vulnerable and exacerbating the negative social impacts of the pandemic. The universal health coverage indicator of SDG 3 on Health and Wellbeing measures the average coverage of essential services for prevention and treatment of infectious and non-communicable diseases for the general and the most disadvantaged population. The score of 60 out of 100 in 2017 (see Sachs et. al., 2021) means that Cambodia was not on-track to achieve its 2030 goals. The pandemic is a further setback in meeting the 2030 goals but the greater awareness of the importance of health system strengthening and the experience mobilizing additional resources for healthcare and social protection during the pandemic may help create momentum for Cambodia to catch up.

Challenge No. 2 – Sustaining future growth

While the economy returned to positive growth in 2021 and is expected to pick up further in 2022, long-term growth will depend on public policy choices. To achieve the high rates of growth seen before the pandemic, Cambodia will need to implement a well-targeted programme of investments and reforms.

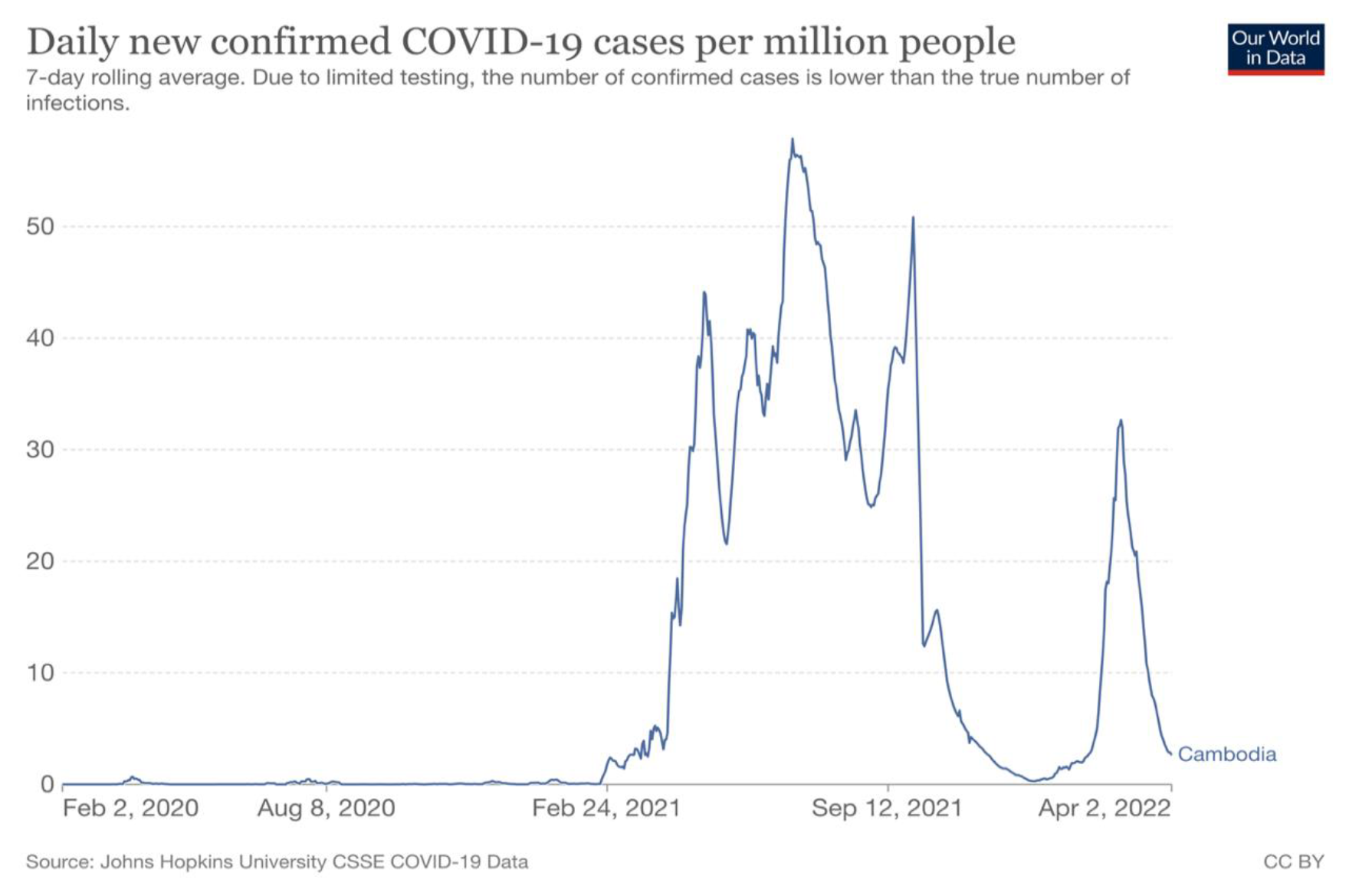

During 2010-2019, Cambodia’s economy grew by more than 7 per cent per annum on average, making it one of the fastest growing countries in the world. This growth was initially fueled by large inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI), strong growth in garment manufacturing and tourism, and rural-urban migration of workers from agriculture into manufacturing and services. However, over time the sources of growth shifted to become increasingly reliant on construction and real estate, which was unsustainable. Property development boomed as investors sought to capitalize on rising urbanization, strong demand from foreign buyers, and the development of Sihanoukville as a hub for gambling and coastal tourism (see Menon, 2022).

The construction and real estate sectors accounted for 19.0 per cent of all growth in 2010-2019 and accounted for 22.5 per cent of total GDP in 2019 (Figure 2). Having accounted for only 4.8 per cent of FDI inflows in 2011, FDI into construction increased steadily to reach 18.8 per cent in 2019. While prices for residential and commercial property remained below regional comparators, the investment boom led to a growing problem of over-supply that has been exacerbated by reduced demand due to COVID-19.

The construction and real-estate sectors cooled significantly in 2020-2021. The close linkages between construction, real-estate, and the financial sector mean that further corrections in the property market could spill over to the rest of the economy. Even if the property and real-estate sector can achieve a soft landing, it is unlikely to be a major source of growth in the medium term. Cambodia will therefore need to rely on productivity improvement and upgrading of agriculture, manufacturing, and other services as the main drivers of growth going forward. Achieving this will require continued investments in infrastructure and human resources as well as reforms to reduce transaction costs and facilitate private investment.

Figure 2.

FDI inflows to construction, real estate, and accommodation ($ million), and as a share of total FDI (%)

Source: Author’s estimates using data from Royal Government of Cambodia.

Significant investments are already underway to improve competitiveness. The Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville expressway, which will halve travel time between the two cities, is due to be completed in 2022, while construction of new airports to serve Phnom Penh and Siem Reap is progressing well. The government has also implemented reforms to reduce the cost of doing business. An online business registration service was launched in 2020, followed by an online licensing platform and a new investment law in 2021. The new investment law includes enhanced incentives to stimulate skills development and investment in high-tech industries, but it will not become fully effective until implementing regulations have been approved.

In addition to economy-wide interventions, the government should also consider sector-specific initiatives to boost growth. Cross-country comparisons suggest that much of the potential benefit of moving workers from agriculture into other sectors have already been realized. While the inter-sectoral transfer is usually associated with a one-off increase in the level of productivity, future growth will require adoption of improved technologies and an intra-sectoral reallocation of factors towards production of higher-value differentiated products or higher value-added activities.

Exports of agricultural products have been growing steadily and the Cambodia-China Free Trade Agreement (CCFTA) and a forthcoming agreement with South Korea offer additional opportunities to expand agricultural exports. To realize this potential, Cambodia will need to strengthen the infrastructure and institutions for trade in agricultural products. This includes development of laboratory and food safety capacity as well as specific sanitary and phyto-sanitary protocols for food exports (See Roeun and Hiev, 2022). There is also scope for well-targeted public policy to support innovation in agricultural production and food processing. This includes greater use of digital technologies, as well as introduction and dissemination of more advanced production technologies.

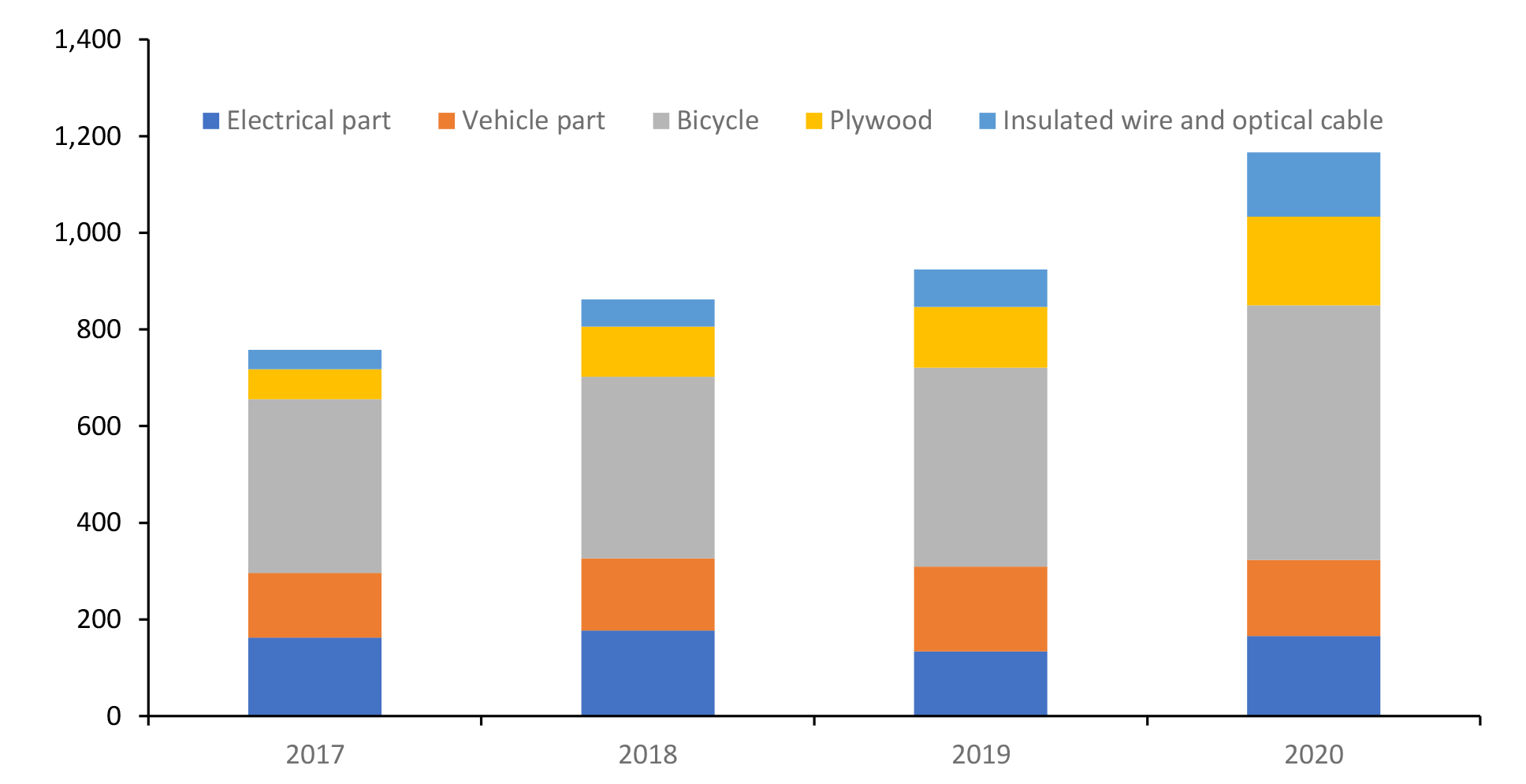

In the manufacturing sector, strong growth in exports of garments, travel goods and footwear (GTF) and approval of new GTF FDI projects in 2021 and Q1 2022 suggest that Cambodia retains a competitive advantage in this sector. However, this is likely to be gradually eroded by rising labour costs and the eventual loss of trade preferences following LDC graduation. While the GTF sector accounted for 57.6 per cent of merchandise exports during Q1-Q3 2021, non-GTF manufacturing exports have been growing rapidly (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Non-garment manufacturing exports, $ million

Source: Author’s estimates using data from Royal Government of Cambodia.

To sustain this growth, Cambodia should implement measures to strengthen the efficiency and competitiveness of its special economic zones (SEZs) and industrial parks (see Warr and Menon, 2016). Potential measures include adoption of voluntary frameworks to enhance SEZ’s environmental sustainability, improved regulation and facilitation of firms operating in SEZs, and promotion of industry clusters to encourage agglomeration effects. Developing industry-relevant skills will also be crucial, and so the government should collaborate with business associations and manufacturers to develop industry skills transformation maps that can be implemented through public-private partnerships.

Tourism recovery and the shift to higher-value tourism can also contribute to growth but Cambodia will need to improve its competitiveness to achieve this. The government is currently implementing a phased tourism sector recovery plan spanning 2020-2025. Visitor arrivals have increased following the re-opening of borders but remain below 10% of pre-COVID levels. The pandemic is expected to lead to long-lasting changes in tourism demand including increased emphasis on social and environmental sustainability (ADB, 2022). Cross-country comparisons suggest that Cambodia lags on key dimensions of tourism competitiveness needed to capitalize on the shifts in demand. For example, Cambodia ranked 98th in the world Economic Forum’s 2019 Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report and was the lowest ranked country in Southeast Asia, with notable gaps and weaknesses on environmental sustainability, human resources, and tourism service infrastructure.

Challenge No. 3 – Rebalancing the financial sector

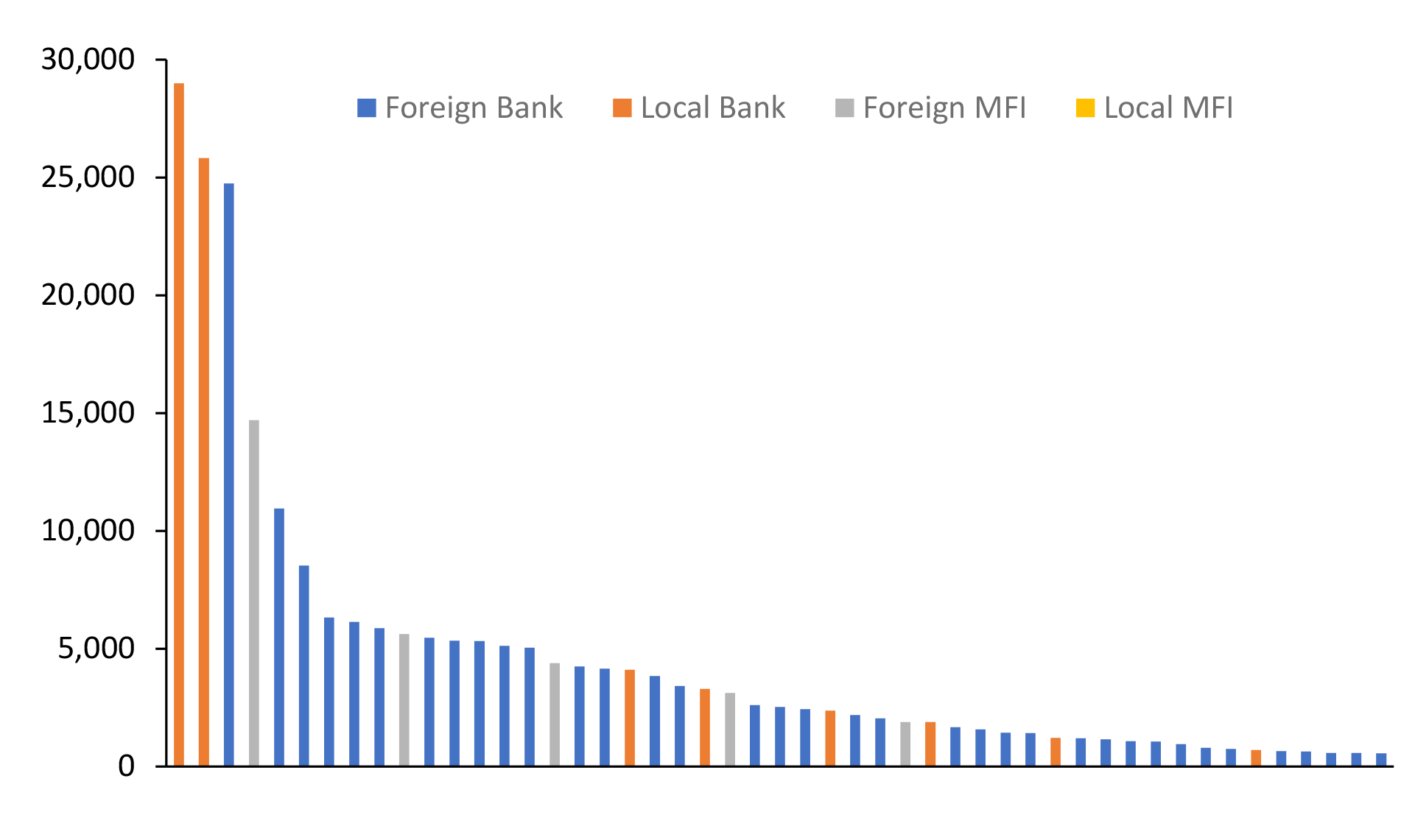

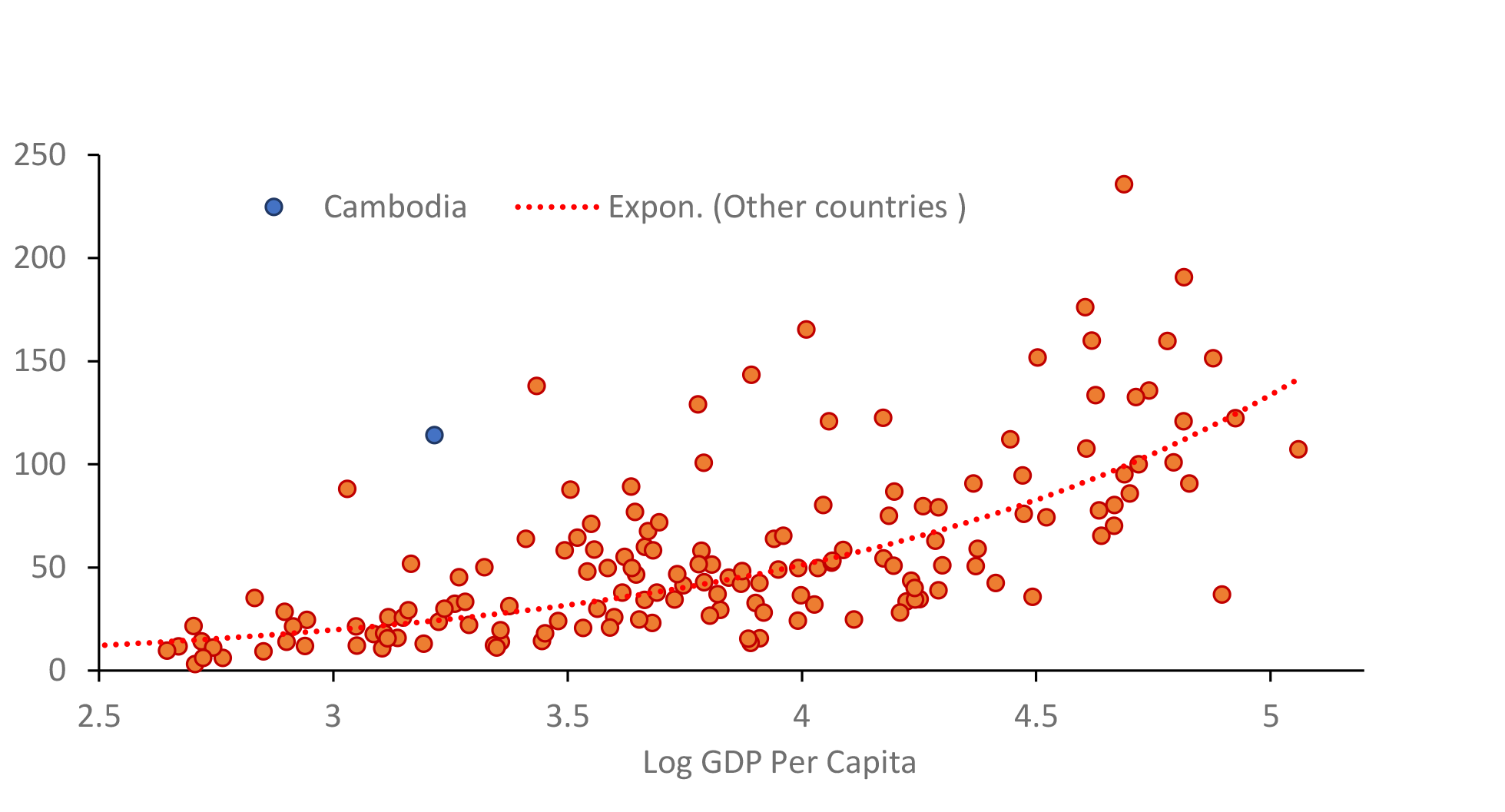

An open and facilitating approach to regulation has supported rapid financial sector growth. By 2020, Cambodia had 59 licensed banks and 79 licensed microfinance institutions. It is notable that some of the largest institutions have either full or majority local ownership (Figure 4). Private sector lending has also increased, very rapidly growing at an average rate of 26 per cent per annum during 2010-2019. This growth saw the ratio of private sector credit to GDP almost quadruple from 28.1 per cent in 2010 to 97.8 per cent in 2019 (Figure 5). Despite efforts to promote local currency usage, Cambodia’s financial system has remained highly dollarized and has significant reliance on overseas funding.

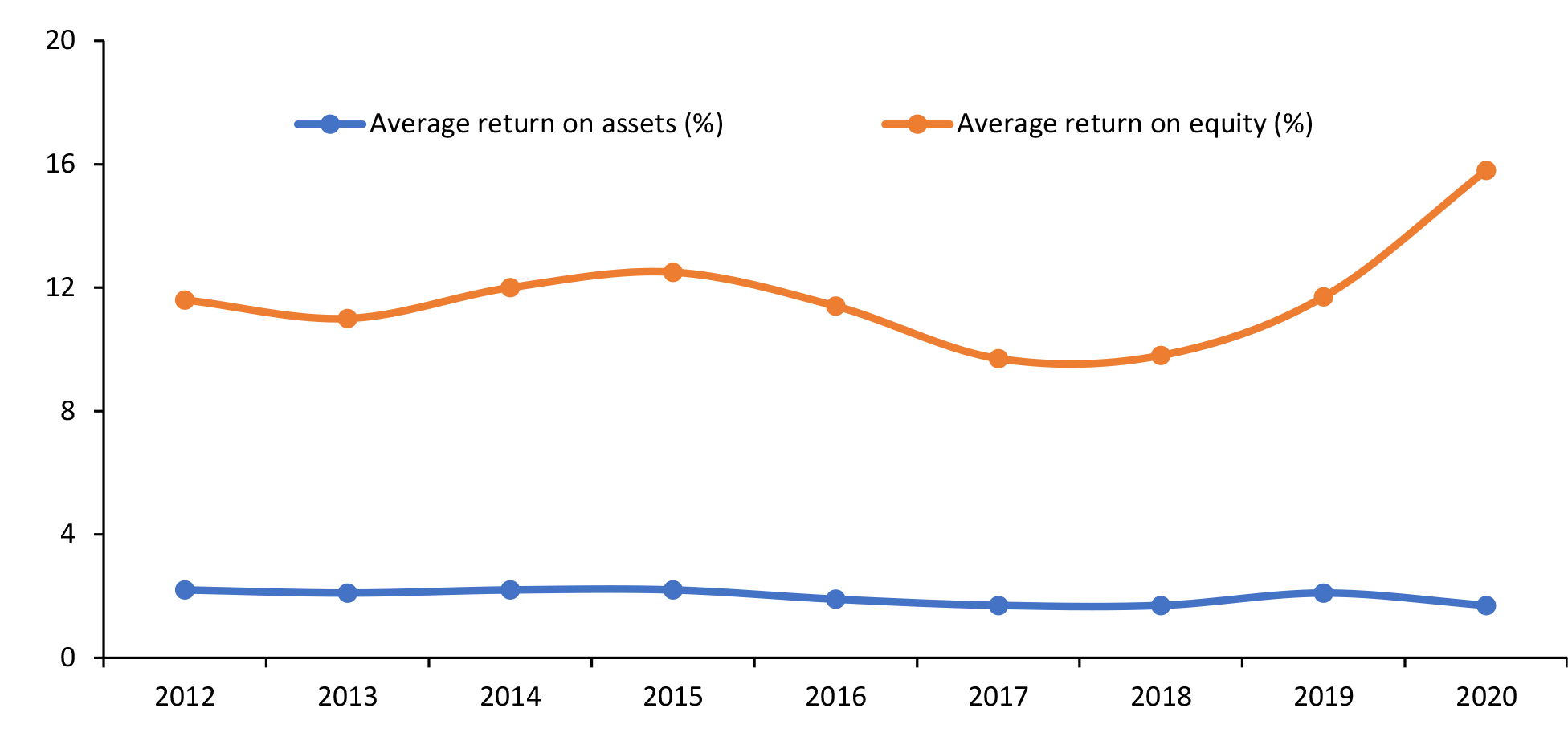

While rates of non-performing loans remained low, there was a moderate decline in the profitability of financial institutions during 2015-2018 (Figure 6). Such declines in profitability can be a leading indicator of increased risk of financial sector distress (Thegeya and Navajes, 2013). In the banking sector, the rapid growth in lending coincided with an even faster growth in lending for construction and real-estate activities linked to the property boom.

Figure 4.

Total assets of selected Cambodian financial institutions in 2019 (KHR million)

Source: Author’s estimates using data from Royal Government of Cambodia.

Figure 5.

Ratio of private sector credit to GDP (%) 2019

Source: Author’s estimates using data from Royal Government of Cambodia.

Figure 6.

Average return on assets and equity of licensed banks in Cambodia (%)

Source: Author’s estimates using data from Royal Government of Cambodia.

Meanwhile in the micro-finance sector, growth in total lending was accompanied by increased loan sizes and growing concern about over-indebtedness of individuals and households (Cambodian Microfinance Association, 2021).

Recognizing the scale of the economic impacts arising from COVID-19, the National Bank of Cambodia (NBC) moved quickly to introduce a package of regulatory forbearance measures. This included a deferral of the planned increase in the bank’s capital conservation buffer and a loan restructuring programme. The restructuring programme was initially targeted at sectors directly impacted by COVID-19 but was quickly expanded to cover all private lending. Under the programme, banks and MFIs could suspend loan interest and principal repayments and adjust the schedule of repayments without reclassifying a loan as non-performing. This enabled banks and MFIs to accommodate borrowers’ needs for flexibility without large-scale provisioning that would have constrained new lending.

Uptake of the loan restructuring programme has been significant. By end 2021, $5.2 billion in loans had been restructured, equivalent to 12.9 per cent of total private sector lending, and 19.9 per cent of GDP. At the same time, new lending continued to grow. As a result, the total stock of private sector lending increased by 52.9 per cent during 2020-2022, with loans to businesses rising 47.6 per cent while personal loans rose by 73.6 per cent. The restructuring programme was extended several times and is now due to end in June 2022. While reported NPLs have remained low to date, the proportion of loans that are non-performing is likely to increase as the restructuring programme is phased out. No data on the distribution of restructured loans by bank or sector have been published but NBC carried out on-site supervision and stress tests in Q4 2021 to get a better understanding of possible risks. It has also instructed banks to postpone dividend payments in order to retain capital and has encouraged some banks to increase their capital base.

A related concern is that some banks, including large locally owned banks have quite high exposure to the construction and real estate sectors. The growth of the property sector has also been associated with increased shadow banking by real-estate developers. A new Non-Bank Financial Services Authority has been established to strengthen regulation and supervision but will need time to become fully operational. Cambodia’s authorities have also been encouraged to accelerate work on the establishment of a deposit protection scheme, implement measures to prevent money laundering, and clarify the framework for bank resolution (IMF, 2021b).

The recent pace of credit growth cannot be sustained indefinitely, however, and has led to growing concerns about over-indebtedness. The rise in imported inflation through supply chain disruption and increase in energy prices raises concerns over domestic inflationary pressures. However, a sudden tightening in the availability of credit would have a significant impact on economic growth.

Cambodia’s authorities will therefore need to carefully monitor the health of banks and MFIs as the forbearance measures are phased out and be ready to intervene as needed to maintain financial sector stability. Systemically important banks with concentrated exposure to construction and real-estate should be closely monitored. A staged increase in minimum capital requirements could also be used to promote consolidation in the banking and microfinance sectors but would need to be managed carefully.

Summary and Conclusions

Cambodia has been heavily impacted by both the direct effects on health from the COVID-19 virus and from measures designed to curtail its spread. Two years after the pandemic, however, Cambodia lead ASEAN in moving ahead with re-opening unilaterally. An impressive vaccination campaign and pragmatic economic policies have helped position the country for economic recovery. However, risks remain, and three key challenges must be addressed to support post-pandemic recovery and long-term growth in an increasingly uncertain global economic environment.

The first relates to maintaining health security and the need to strengthen the healthcare system. The capacity of the healthcare system remains one of the lowest in Asia. Had there been more healthcare capacity to work with, the government could have employed a more targeted approach in managing the outbreak and reduced the toll on the economy and livelihoods.

The second challenge is to identify and support new sources of growth. While the construction and real estate sectors accounted for about a fifth of growth in the decade leading up to the pandemic, this is unsustainable and will not continue. Future growth will need to come from diversification within agriculture and manufacturing, with a move towards higher value-added activities supported by greater investment. Foreign investment is likely to play a key role in enabling this transformation and improving domestic infrastructure, and upgrading local skills will help ensure that Cambodia is well positioned to attract high quality investment. A revival in tourism will also aid recovery but will also need more investment for upgrading to cater to higher-spending tourists.

The third and last challenge relates to managing financial sector risks. The forbearance measures related to the pandemic, cooling of the property sector and slowdown in growth have increased the indebtedness of households and firms. The winding back of the support measures needs to be carefully managed to avoid a financial meltdown, while increased regulation and supervision is required for long-term financial sustainability.

References

- ADB. 2022. COVID-19 and the Future of Tourism in Asia and the Pacific. Manila

- Cambodian Microfinance Association. 2021. CMA Lending Guidelines Interim Report, May 2021. Phnom Penh.

- Freedman, David and Jayant Menon. 2022. “Cambodia’s Post-Pandemic Recovery and Future Growth: Key Challenges” Perspective 2022/40, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

- IMF. 2021a. Staff Report of the 2021 Article IV Consultation. Washington DC

- IMF. 2021b. 2021 Article IV Consultation, Press Release and Staff Report. Washington DC:

- IMF. 2022. 2022 Article IV Consultation, Press Release and Staff Report. Washington DC:

- IMF Staff Completes 2022 Article IV Mission to Cambodia

- Menon, Jayant. 2021a. Is Cambodia’s Endemic Covid-19 Approach Sensible? Fulcrum, 9 November.

- Menon, Jayant, 2021b. New Covid-19 Strains: Domestic Surveillance, Not Selective Travel Bans, Will Go A Longer Way” Fulcrum, 10 February.

- Menon, Jayant. 2022. The Belt and Road Initiative in Cambodia: Costs and Benefits, Real and Perceived. Paper presented to the East Asian Economic Association Conference, Sunway University, September 2022.

- Roeun, Narith and Hokkheang Hiev. 2022. Agricultural Exports from Cambodia to China: A Value Chains Analysis of Cassava and Sugarcane. In Menon, Jayant and Vathana Roth (eds.), Agricultural Trade between China and the Greater Mekong Subregion Countries: A Value Chain Analysis, Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Sachs, Jeffrey, Guido T.-Schmidt, Christian Kroll, Guillame Lafortune and Grayson Fuller. 2021. Sustainable Development Report 2021 – The Decade of Action for the Sustainable Development Goals, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thegeya, Aaron and Matias Costa Navajas. 2013. “Financial Soundness Indicators and Banking Crises,” IMF Working Papers 2013/263, International Monetary Fund.

- Warr, Peter and Jayant Menon. 2016. Cambodia’s Special Economic Zones. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies 33(3), 2016, pp. 273-90.

- World Economic Forum. 2019. The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report, 2019. Geneva

- World Health Organization. 2022a. COVID-19 Joint WHO-MOH Situation Report 82. Phnom Penh

- World Health Organization. 2022b. Strategic Preparedness, Readiness and Response Plan to End the Global COVID-19 Emergency in 2022, WHO/WHE/SPP/2022.1, Geneva.